Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Without ever touching a shovel, pickaxe or any traditional tool of the archaeological trade, a historian and three economists have helped discover 11 lost cities from ancient Assyria.

Using data mined from thousands of cuneiform tablets that recorded trade among ancient Assyrian merchants, a team of researchers has come up with a comprehensive picture of what trade routes looked like 4,000 years ago.

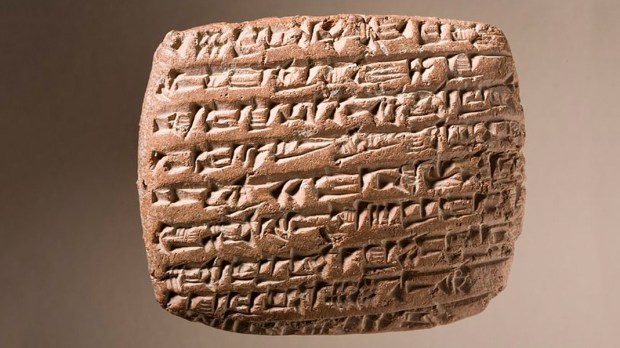

The Bronze-Age tablets contain “business letters, shipment documents, accounting records, seals and contracts,” according to the working paper by historian Gojko Barjamovic, and economists Thomas Chaney, Kerem A. Cosar and Ali Hortacsu.

The Washington Post, in its report on the paper, said that traditionally these tablets would be analyzed for qualitative information, such as the description of landscapes or any mention of the distance between cities to help locate sites mentioned within them.

Instead, the co-authors of the papers decided to use a quantitative analysis based on trade interaction among the 26 ancient cities whose trades are recorded on the 12,000 clay tablets.

The researchers were able to help pinpoint the location of the 11 lost cities by using one key insight, according to the Post report: In the ancient world, because trade was so difficult, cities that were located closer together traded more, while cities that were further apart traded less.

For example, if we know the location of the ancient city of Kanesh, but don’t know the location of those lost cities of Kurburnat and Durhumit, we can determine that whichever of these cities trades more often with Kanesh is closer to Kanesh.

Plugging in the data culled from the cuneiform texts into their algorithm the researchers were able to estimate the locations of the 11 lost cities mentioned in them, sometimes confirming, but sometimes calling into question the previous work of historians.

“For a majority of cases, our quantitative estimates are remarkably close to qualitative proposals made by historians,” the authors wrote. “In some cases where historians disagree on the likely site of lost cities, our quantitative method supports the suggestions of some historians and rejects that of others.”

Their method is not 100 percent precise, however. To test it, the researchers ran the model against the location of the known ancient cities to see if it would accurately pinpoint them.

The results: two out of three cases were right on the money.

Perhaps traditional historians using qualitative analysis need not worry about economic models making them obsolete.

On the other hand, two out of three ain’t bad. Time to get out the shovels and pickaxes, and start digging for those 11 lost cities?