The

isn’t like other songs which tell the story of the Nativity. It was written by the Jesuit martyr St. Jean de Brébeuf,a missionary to the Huron tribe of Native Americans, and the details are different than the usual scene.‘Twas in the moon of wintertime,

when all the birds had fled,

that mighty Gitchi Manitou

sent angel choirs instead;

Before their light the stars grew dim,

and wondering hunters heard the hymn:

Jesus your King is born,

Jesus is born, in excelsis gloria.

The setting is North America, and though the story is familiar, the images are not. Here, Jesus isn’t born in a stable, but “in a lodge of broken bark.” It’s not the wise men who visit him, but “chiefs from far,” and hunters, not shepherds, who hear the angels. Jesus isn’t laid wrapped in swaddling clothes–instead, “a ragged robe of rabbit skin enwrapped his beauty round.” The song feels like another version of a beloved children’s book–same plot, different illustrator.

Of course, Christ was really born in Israel. It was shepherds who first heard the news. Mary really did wrap him in swaddling clothes. But on the other hand, how many of our own cultural details that we add into the Nativity story are historically true?

Jesus wasn’t blonde, as he’s often depicted, and he certainly wasn’t Caucasian. It’s very rare that it snows in Bethlehem, even if Jesus were born during wintertime. And that’s okay. We like to tell the story in a way that brings it right to our front door, so to speak.

The Catechism teaches that the offering of the Eucharist is the same sacrifice of Christ’s death on the cross. (1367) The crucifixion happened long ago, but the sacrifice is present, not past tense.

Read more:

Why is Sunday Mass important, anyway? The pope explains

Well, we’re doing the same kind of thing here, though symbolically, when we tell these stories in a way that connects them with our own experiences. We are trying to draw them through history into the present day. Jesus was only born once, but his human nature stays with us to this day, so telling the stories in the present tense conveys an essential truth: God is with us, not only then, but now as well.

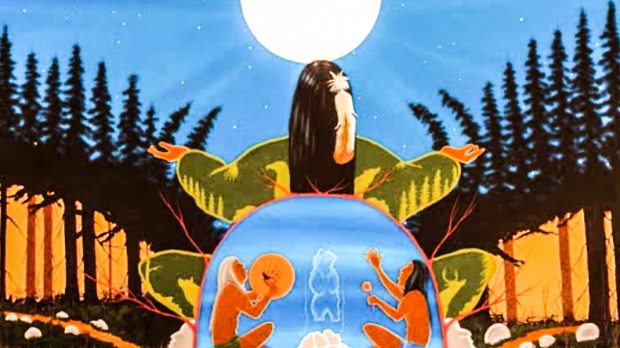

That’s what St. Jean de Brébeuf was trying to convey to the Hurons. It’s what Our Lady of Guadalupe was saying too, when she appeared to St. Juan Diego, not as a Palestinian, but as a Native American like himself. It’s a theme that God keeps repeating, over and over again, right down to taking it as his very name, Emmanuel.

Before Jesus could even talk, he was telling us, “God is with us.” It’s the last thing he says, too, before ascending into Heaven: “I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

Read more:

Paddles and penance: Diverse group uses canoe trip to promote healing

The Huron Carol, different as it is, reminds us of God’s desire to meet us wherever we are, through whatever experiences we’ve had. God is constantly trying to convince us that he actually is “like us in all things but sin,” as St. Paul said. Our Lady of Guadalupe had the same message: “Am I not here who am your Mother?… Are you not in the folds of my mantle? In the crossing of my arms?” She is so close to us! Not standing next to us, but wrapping us up within her very cloak.

Christmas is the feast of the Incarnation, when God took on human nature once and for eternity, so that not even our humanity could stand between us. It’s a good time to remember, then, that God is much closer to you and me than we think–and much closer to other people than we like to acknowledge, too. I’m grateful for the Huron Carol, which yearly reminds me of this central truth.

Read more:

Nicholas Black Elk: This Sioux medicine man may be recognized as a saint