If you enjoyed a glass of pasteurized milk this morning at breakfast, thank Louis Pasteur for discovering how to preserve milk so that it did not kill you with tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever or another nasty disease.

Louis Jean Pasteur was born in eastern France, the third child of a poor tanner, Jean-Joseph Pasteur, and his wife Jeanne-Etiennette Roqui. He came from a long line of peasants, and was only an average student, preferring fishing and sketching to studying.

However, Pasteur developed an interest in science, and after receiving degrees in philosophy and science – though he failed his first science exam and did poorly in chemistry – he moved to Paris to devote his life to scientific disciplines, with financial assistance from his father.

Pasteur’s first major discovery was molecular dissymmetry in organic substances (now known as molecular chirality). He wrote to his sisters, “If by chance you falter on the journey, a hand will be there to support you. If that should be wanting, God, who alone would take the hand from you, would accomplish the work.”

Six years later, after two professorships in physics, Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg. It was there that he met and fell in love with Marie Laurent, daughter of the rector. They were married in May the following year — aged 26 and 23, respectively — and Marie became his indispensable scientific assistant. The Pasteurs had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood. His son Jean-Baptiste fought in the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1854, Pasteur was named dean of sciences at Lille University. Two years later, a local wine-maker, the father of one of Pasteur’s students, asked for his advice on fermentation. Pasteur began to research the fermentation process and proved that it was not caused by decomposition, but by yeast. He also found that oxygen decreases fermentation – this has become known as the Pasteur effect.

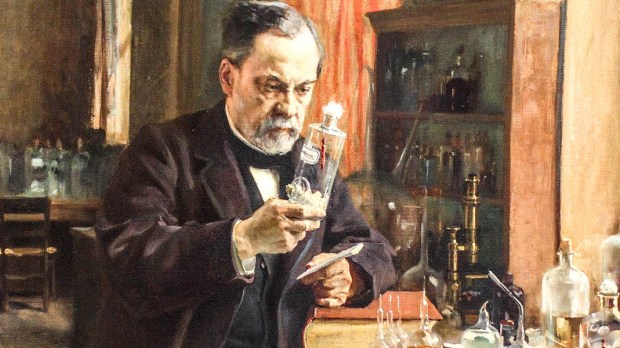

Pasteur realized that the growth of micro-organisms spoiled beverages like milk, beer and wine. He created the process of heating liquids to kill bacteria latent in them. This became known as pasteurization.

Pasteur quipped, “dans les champs de l’observation, le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés (In the field of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind).” His experiments led to the acceptance of germ theory, which had earlier been unsuccessfully posited by Ignaz Semmelweis.

Another great contribution Pasteur made was to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation, that life could be produced out of non-life (like maggots appearing in corpses). This theory, also called abiogenesis, was used by Charles Darwin to propose that the first life forms emerged from a little pond with a mix of substances. Pasteur’s experiments demonstrated that this was impossible.

After treating chicken cholera, Pasteur also created the vaccines for anthrax and rabies, laying the intellectual foundations for immunology. In 1887, he founded the Institut Pasteur (Pasteur Institute) in Paris, which continues important work against infectious diseases. Among other contributions, the institute was the first to isolate HIV.

Pasteur wrote: “Happy the man who bears within him a divinity, an ideal of beauty and obeys it; and ideal of art, and ideal of science, an ideal of country, and ideal of the virtues of the Gospel.” These words are graven above his tomb in the Institut Pasteur, where his body was moved after first being buried in the Cathedral of Notre Dame following a state funeral.

Having suffered a stroke, Pasteur died holding his rosary, while having the life of St. Vincent de Paul read to him, because he hoped that his work, like St. Vincent’s, would save suffering children. Indeed, we owe an immense debt to Pasteur; let us pray for the souls of his family.