New York has always been a multicultural city. As early as the 1600s, some two dozen languages were spoken therein. And African-Americans have been a constant in New York life, right from the start. But not all came of their own will. As late as the year 1800, the city still had approximately 2,500 slaves (slavery would be banned in New York State in 1827).

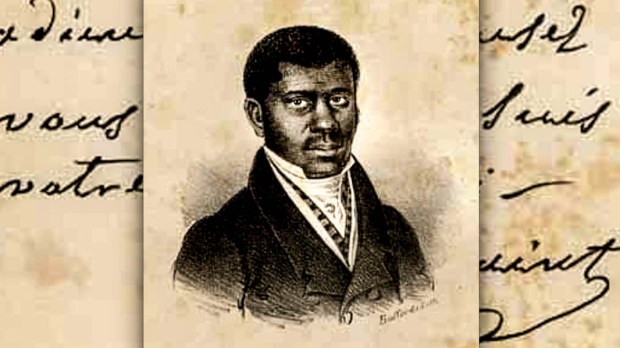

Many slaves were from Haiti, a country born out of revolution. Throughout the 1790s, thousands of the island’s white residents fled to America. Among them were plantation owner Jacques Berard and his wife, who brought five slaves with them, including Berard’s domestic servant, Pierre Toussaint. They expected their exile in New York to be temporary, but events on the island prevented their ever returning.

Haiti was then the single greatest market for Europe’s slave trade. “Field-hand life,” one historian notes, “was brutal.” A visitor witnessed barely clad men, young and old, working under a blazing sun and brutalized by overseers. Under such conditions, nearly half of all men died before age 40. In short, the colony was “a dormant volcano” that would finally erupt with a slave revolt in 1791.

Pierre, born on the Berard plantation, was fortunate enough to avoid the hellish existence of a field slave. As a domestic servant, he lived in relative comfort. He was even allowed access to the family library, where he encountered classic Catholic works such as The Imitation of Christ. This became his favorite book, which he quoted from memory into old age.

In New York, Monsieur Berard suggested Pierre take up hairdressing to help support the family. He learned the profession quickly, and over time he became “the fashionable coiffeur of the day.” Pierre was intensely loyal to the Berards. After Jacques died penniless, he took care of his widow until her own death. Shortly before that event, she freed Pierre.

As Pierre’s clientele grew, he became one of New York’s foremost black entrepreneurs. He bought a house in downtown Manhattan, and invested in real estate and banks. Although comfortably set, he still worked well into old age. “I have enough for myself,” he said, “but not enough for others.” Helping others, regardless of ethnicity, was a constant theme in his long life.

A devout Catholic, for some 60 years Pierre attended the morning Mass at St. Peter’s Church on Barclay Street. (Founded in 1785, St. Peter’s was the first Catholic church in New York State.) During its early years, he also helped support St. Vincent de Paul, New York’s first French parish, on Canal Street (it later moved to West 23rd Street).

A benefactor of the Catholic Orphan Asylum, he and his wife raised several homeless African-American children. In several cases, he purchased freedom for slaves (including his own relatives). During one of the city’s numerous epidemics, a biographer writes:

. . . when the yellow fever prevailed in New York, by degrees Maiden Lane was almost wholly deserted, and almost every house in it closed. One poor woman, prostrated by the terrible disorder, remained there with little or no attendance, till Toussaint day by day came through the lone street, crossed the barricades, entered the deserted house where she lay, and performed the nameless offices of a nurse, fearlessly exposing himself to the contagion.

Toussaint was one of New York’s most respected citizens, and contemporaries recalled his “innate sense of personal dignity,” “his exquisite charity and consideration for others,” and “his tender compassion for all.” One woman stated:

I saw how uncommon, how noble, was his character. It is the whole which strikes me when thinking of him; his perfect Christian benevolence, displaying itself not alone in words, but in daily deeds; his entire faith, love, and charity; his remarkable tact, and refinement of feeling; his just appreciation of those around him; his perfect good taste in dress and furniture—he did not like anything gaudy and understood the relative fitness of things.

Nevertheless, Toussaint was no stranger to racism. Even in old age, he walked to clients’ homes, since he was banned from riding the horse-cars. Neither were churches immune from prejudice. On one occasion, an usher refused him a seat at Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street (the present cathedral was completed in 1879). White Catholics, unintentionally patronizing, meant to praise him by calling him a “Catholic Uncle Tom.”

At a time when the slavery question was on the rise, biographer Arthur Jones notes that Pierre “never was willing to talk on the subject.” At this time, many Catholics avoided the antislavery movement because many abolitionists were anti-Catholic. On the rare occasion he discussed the subject, he said: “They have never seen blood flow as I have.”

On June 30, 1853, Pierre died at age 87. At his funeral Mass at St. Peter’s, many of the attendees, a biographer writes, had “eyes glistening with emotion.” In his sermon, Father William Quinn noted:

Though no relative is left to mourn for him, yet many present feel that they have lost one who always had wise counsel for the rich and words of encouragement for the poor. And all are grateful for having known him . . . There were very few left among the clergy superior to him in devotion and zeal for the Church and for the glory of God; among laymen, none.

In 1991, Cardinal John J. O’Connor introduced Pierre’s canonization cause, and he was reinterred at the new St. Patrick’s Cathedral (the only layperson so honored). During his visit to St. Patrick’s, Pope John Paul II declared Pierre Venerable. Cardinal O’Connor himself considered it “a great privilege” to be buried alongside Pierre. From slave to entrepreneur, a benefactor and friend of the poor, O’Connor added: “If ever a man was truly free, it was Pierre Toussaint.”

First published in 2011, reprinted here with kind permission of the author.