Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

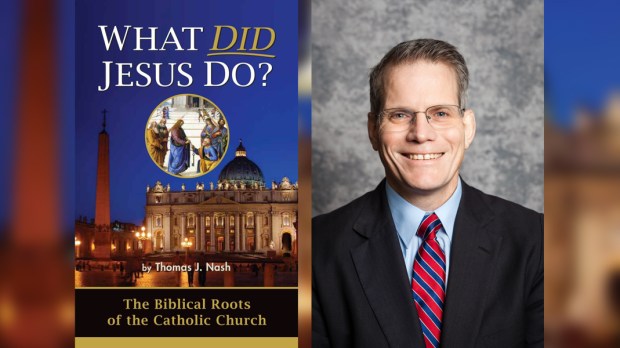

I was prepared to like What Did Jesus Do? The Biblical Roots of the Catholic Church. That was because the author, Thomas J. Nash, made it personal by jotting a note to me inside the cover. That hardly ever happens. I warmed up to it immediately. More, he included a personalized post-it note, stuck in the same place. That has never happened. Honest, I really wanted to like it.

Nash has written a spirited a defense of dogmatic Catholicism. I might even go so far as to describe his work as largely Scholastic. Scholasticism, among other things, is marked by careful and at times pedantic argumentation. Nash adopts the same approach, so far as I can tell: define the faith, describe the opposite (sometimes polemically) and defend that faith against all comers whenever found.

Unfortunately (explained in a footnote, pp. 25-26), this includes direct attacks against the Protestant Reformation and the Reformers (those terms, he says, are “used only because they are familiar”). He aims to make clear (in the same footnote), “that any hope the Reformers had for true reform ended, when they rejected the divinely given authority of the Pope and began to establish other doctrinal novelties.”

He promises at the same time to “strive to offer hope for an epic reunion between Catholics and Protestants, as well as advancing the mission to make disciples of all nations otherwise.” He suggests, in the final chapter, taking Mother Angelica’s advice and opening more Eucharistic Adoration chapels, with parishes hosting adoration evenings for inquirers. Not a thing wrong with that, but I’ll just let it sit there.

I started getting grumpy with What Did Jesus Do? when Martin Luther entered the presentation. I once was a Luther fan boy, you know, and I retain some interest in seeing he at least gets a fair shake.

So, contrary to Nash’s footnoted citation (p. 86), no, Martin Luther was not the author of the Augsburg Confession. Philip Melanchthon was the final author and by the time he finished, many hands were in it besides Luther’s, including a conciliatory bishop consulted by Melanchthon, Christopher von Stadion (d. 1543), the bishop of Augsburg (who remained Catholic).

Melanchthon was a philosophy professor at Wittenberg University where Luther taught theology. Luther, in fact, was irritated by Melanchthon’s irenic tone (or maybe it was Bishop Stadion’s) in the final document. Luther would have liked something sharper. Nash made a minor footnote error; not his fault. But I was annoyed. But again, not his fault. I’m a footnote nerd.

Understand, yes, Nash defends Catholicism ably, but perhaps for these days he is doing it from the wrong direction. I honestly doubt that, as an invitation to Catholicism, “dueling dogmas” reaches anyone any more.

Today, 18- to 25-year-olds are the least religious generation in our history. They back away from religion faster than you can say “spiritual but not religious” (which, as a “doctrine,” isn’t doing too well these days, either). These, just make note of it, are the people most likely to confuse Martin Luther with Martin Luther King, Jr.

I am teaching Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults (RCIA) these days. I do not labor at all about what Luther or Calvin or Zwingli did wrong. There is little point to it. People are there not for Luther’s mistakes, but for the Catholic faith. I teach what that faith teaches and, I pray, I do it with joy.

What Did Jesus Do? as I experienced reading it, is “Take No Protestant Prisoners” apologetics. Me, I’m an ex-Lutheran Catholic. Yes, no question, I experienced a call to unite with that Church “best ordered through time,” as a friend described his experience. It is that Church, this Church best ordered through time, that best proclaims a Truth that is true. This call came to me largely because I could no longer find that Truth deeply enough to my satisfaction among the Churches of the Augsburg Confession (as Lutherans are known more formally).

But possession of the Truth that is true requires, I suggest, a becoming humility for having been given that faith. For faith is God’s gift by the Holy Spirit. It cannot be our own creation and we always remain mere stewards of the Truth. “The Church,” as Pope St. John Paul put it, “proposes; she imposes nothing.”

The confidence of Truth carried by the Catholic faith, at minimum, requires recognition we are speaking to one another ― Catholic and Protestant ― as people united in our baptism into Christ. We therefore each share some portion of that unity which is ultimately the unity taught by the Catholic Church. The world of Catholic and Protestant, we may pray, will in God’s time find that accomplished unity Christ demands of ― and promises for ― his Church.