The middle class is always a firm champion of equality when it concerns a class above it; but it is the inveterate foe when it concerns elevating a class below it. ~“The Laboring Classes,” 1840

In 1937, New York City police investigated a vandalism case on West 104th Street and Riverside Drive, where teenagers had toppled and defaced a statue dedicated to Orestes A. Brownson (1803-1876).

After extensive investigation, police couldn’t find anyone who knew who Brownson was.

It turned out that he had a loose connection with Fordham University in the Bronx, so the statue was sent there. But many years later, one Jesuit recalls, students still “hadn’t the vaguest idea” who he was.

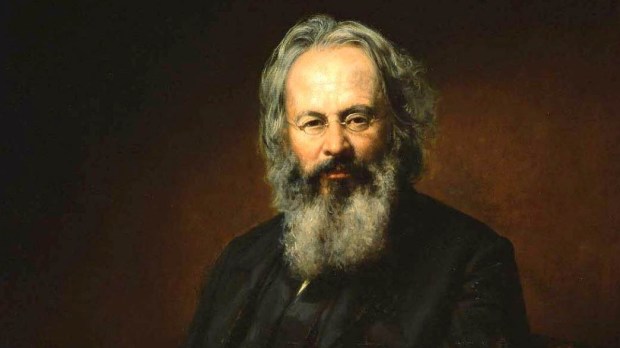

The irony is that Orestes Augustus Brownson was one of the previous century’s foremost intellectuals, involved in every major debate of the time: political, religious, intellectual, with strong opinions on all. (His collected writings number 20 volumes.) A seeker after truth, he joined several churches before finding Catholicism. In time he forged a place for himself as Catholic America’s first great lay intellectual.

Brownson was largely self-educated. Born to a poor Vermont family and raised Presbyterian, at 20 he converted to Universalism, returned to Presbyterianism, and reconverted to Universalism — all in a single year. Ordained in 1826, he ministered in New England. Religiously speaking, the New York Herald commented, “Brownson has blown from all points of the compass.” Peers wondered “what direction his mind would take next.” The one constant, a close friend recalled, was a “passion for truth.”

By the 1830s, he was a Unitarian pastor in Boston. In a time of great political and economic unrest, Brownson believed Christianity must lead the fight for social justice, and he publicly declared Jesus “the prophet of the workingman.” In 1838, he started Brownson’s Quarterly Review as an organ for his views. Its motto was “We Know No Party but Mankind.” (Foes suggested, “We Know No Party but Brownson.”)

A brief foray into political campaigning disillusioned Brownson, who concluded that human action, alone, was incapable of transforming society. “No Church, no reform” was his new motto. He was looking specifically for a Church that would unify, not divide, society. It should offer communion rather than the disunity he saw among various Christian denominations. In short, he wanted a Church that was “catholic,” in the universal sense.

Brownson could not immediately decide whether he should join the Roman or Anglican Church. Through reading and prayer, he came to view Rome as the fullness of revelation and hope for true reform. Ultimately he saw conversion as a matter of “saving my soul.” In early 1844, he began receiving religious instruction from a bishop in Boston, and in October he was formally received. He remained a Catholic for the rest of his life.

As a husband and father of eight, Brownson was ineligible for priesthood, but he found other ways to preach, through his magazine and public lectures. (He remained his own editor because he couldn’t “bear mutilation by any hand but my own.”) He called upon American Catholics to engage the day’s major intellectual and religious issues. “The responsibility of Catholics,” he wrote, “is greater than that of any other class of citizens.”

Brownson saw American democracy as a model for the world. Although he supported the separation of church and state, he insisted that religion had an important role to play in public dialogue. Democracy, he believed, needed a moral basis that only religion could provide. Long before TV and the internet, he warned, “The greatest danger to American society is that we are rapidly becoming a nation of isolated individuals.” Catholicism with its communal emphasis provided a powerful antidote.

At a time when many questioned whether Catholics could be good Americans, Brownson argued boldly that Catholicism was the nation’s best hope:

The Catholic Church comes not to destroy, but to fulfill: to purify, elevate, direct, and invigorate. And as our country is the future hope of the world, so is Catholicity the future hope of our country.

Brownson’s conservatism grew more pronounced with time. But, his biographer Patrick Carey notes, this didn’t mean he “favored the status quo or that he rejected progress and reform.” He was increasingly convinced that the major philosophical issue of the time was the secularization of the Western mind — a notion that may explain the renewed interest in some of Brownson’s ideas among modern conservative thinkers.

Brownson was unafraid to venture his opinion on any issue; philosophy, science, politics, literature, religion: he addressed it all. He considered Charles Dickens’ popularity “one of the worst symptoms of the age.” Charles Darwin, he wrote, was someone to whom “we should refuse even to bid good-day.” He dismissed suffragettes in the belief that a woman was “created to be a wife and a mother.” And while he opposed slavery in principle, he was sadly as racist as his times, writing: “We cannot alter the fact of Negro inferiority.”

Brownson’s Catholic period was no less controversial than those preceding. When asked if he found it a bed of roses, he replied: “Spikes, sir — spikes!”

Some of those spikes may have been of his own making. Quick-tempered and opinionated, he offended casually. He called Jesuit schools “intellectually inefficient” (even though his sons attended them); he accused one bishop of “muddle-headed” philosophy, and labeled an author’s English “far less intelligible” than any “Latin we have ever encountered.”

An equal-opportunity offender, Brownson declared to Protestants that they were not real Christians. During a time of heightened anti-Catholicism, he insulted the Irish by urging them to become better Americans. He was, one author wrote, “too Yankee for the Catholics and too Catholic for the Yankees.” To a friend he privately complained that New York was “becoming more and more Irish,” and soon he moved to New Jersey.

Plagued with poor health in later years, Brownson lived with relatives until his death at age 73. Although he soon vanished from history, scholars have reclaimed his place in recent decades. In a study of conservative thinkers, Russell Kirk placed him high. Jesuit author Raymond Schroth calls him “America’s first great Catholic intellectual,” who defined the laity’s role in public life. For American Catholics, Brownson’s politics are ultimately less important than his work in bringing their faith to bear on modern culture and life, a task we continue to face today.

Previously published online in 2011, reprinted by kind permission of the author. – Ed