On the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this series of articles looks at how the Church responded to this turbulent age by finding an artistic voice to proclaim Truth through Beauty. Each column visits a few Roman monuments and looks at how art was designed to confront a challenged raised by the Reformation with the soothing and persuasive voice of art.

It was on the steps of the Holy Stairs in Rome’s Cathedral of St. John Lateran that Martin Luther had his life-changing revelation that “the just shall live by faith.” Mounting the 28 steps thought to be those that Christ climbed to be judged by Pontius Pilate, Luther came to reject the relics, practices and sites connected with the Roman Catholic Church.

And so began Luther’s battle over the apostolic tradition.

Against the Catholic claim of the rootlessness of Protestant thought, Luther said his teaching was “not a novel invention of ours but the very ancient, approved teaching of the apostles brought to light again.” The Protestants sought not “to have anything new in Christendom” but instead struggled “to hold to the ancient: that which Christ and the apostles have left behind them and have given to us.” They claimed that this teaching had been “obscured by the pope with human doctrine, aye, decked out in dust and spider webs and all sorts of vermin, and flung and trodden into the mud besides, we have by God’s grace brought it out again … to the light of day.”

So, who had the claim to tradition? Which teaching had the martyrs died for? What role did relics play — testimony to ancient history, or were they, as John Calvin wrote in his Treatise on Relics, an “abomination”?

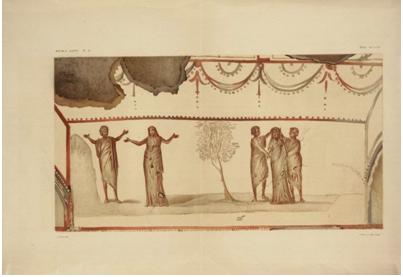

An astonishing find on the Via Salaria on May 31, 1578, gave the Church a potent response. The entrance to one of the Christian catacombs was accidently discovered by some workmen, leading to the underground burial sites with thousands of tombs. These mass graves, lost since the 9th century, were decorated with hundreds of paintings, witnesses to the early Christian Church and its beliefs.

Antonio Bosio, a young lawyer-turned-archaeologist who was close to Philip Neri’s new congregation of the Oratorians, took it upon himself to explore these underground sites. Dubbed the “Columbus of Underground Rome,” his lifetime of work was crowned with the publication, three years after his death, of Roma Sotterranea Cristiana: a guide to the catacombs, complete with illustrations.

Bosio’s first catacomb visit brought him to the cemetery of Domitilla, where he saw (and signed) an image of Christ transmitting his teaching to the apostles with St. Peter seated in the direct line of his hand.

Bosio also identified congested spaces where the graves of the faithful were clustered around the tombs of martyrs, in the hopes of intercession on the Day of Judgment. These images provided powerful witness to a tradition of scriptural interpretation, including pictures taken from the stories of Susanna in the Book of Daniel, which had been expunged from the Protestant Bible.

The most exciting find, however, took place in 1599, on the eve of the great Jubilee Year of 1600, when the incorrupt body of St. Cecilia was found in what had been her home in Trastevere. Martyred in the 2nd century, St. Cecelia, a virgin martyr, was originally interred in the catacomb of St. Callistus. In 821, Pope Paschal had removed her body from the catacombs which were about to be closed and sealed, and placed it in a crypt in the church he was building in her honor, in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome. In 1599, a commission opened the tomb and found her body intact.

Papal artist Stefano Maderno was immediately commissioned to make a sculpture of this saint who testified to the virtue of chastity in an age when licentiousness reigned, who gave away her considerable material wealth in an era of luxury, and who worked in close collaboration with Pope Urban I to convert her husband and brother-in-law to the true faith.

The graceful statue shows a sleeping Cecelia inside a space identical to that of her tomb. The fluid lines convey serene peace, but her sharply-turned head and the thin slice mark on her neck reveal the brutality of her murder. Her hands rest close to the viewer, clasped in the age-old gesture of belief in the Trinity (three fingers extended) and in Christ’s dual nature as God and man (the open finger and thumb on her left hand).

Alongside the rediscovery of the tombs and bodies of the martyrs, the stories of their passions were undergoing an overhaul by Oratorian Cardinal Cesare Baronio in the new Roman martyrology.

The savage nature of the Roman persecutions grew in relevance as the excavations of the silent tombs continued. The thousands of graves nestled side-by-side bore quiet witness to the fact that although many in the community had died under vicious persecution, they had found the peace they had sought in Christ.

The brutality of their deaths became fodder for many churches frescoes, especially those where young missionaries were to be trained: priests who would go out to the hostile lands and often die gruesomely themselves as they tried to bring about conversions. The most powerful example is the surround-sound style martyrdom cycle in the church of St. Stephen in the Round, executed by Pomarancio in 1583 for the German-speaking Jesuits who would be sent back to Germany to try to evangelize the Protestants.

Starting with St. Stephen, 34 large panels encircle the viewer showing the varied and violent deaths of the martyrs. From being thrown to the beasts, to being hacked to death with machetes, or boiled in oil, or crushed by giant blocks of stone, Christians had known the gamut of human cruelty. These images graphically recalled what the early commitment to the faith looked like in the face of persecution by the powerful Roman Empire.

These relics, frescoes and other testimonies were housed in churches, some of them ancient, with roots going back to the times of Saints Peter and Paul. The Catholic Church realized that even more than peering at the tombs or looking at pictures, standing in a space where the Eucharist had been celebrated for 1,500 years expressed the continuity of the ancient teaching better than anything else.

Prelates were enlisted to breathe new life into the oldest churches: Cardinal Baronio rebuilt the ancient house church of Saints Nereus and Aquileus using more vivid martyrdom imagery; St. Charles Borromeo redesigned St. Praxedes, adding special galleries where the most important relics could be displayed as well as personally spending nights in prayer in the confessio under the altar before the tombs of martyrs taken from the catacombs. Cardinal Enrico Caetani remodeled the 4th-century church of Santa Pudenziana, home of the sisters Praxedes and Pudenziana, where St. Peter had lived when he first arrived in Rome. These sisters were known to have gathered the blood of the first martyrs, collecting it in a well. Cardinal Caetani commissioned Giovanni Paolo Rossetti to paint these two sisters, who were baptized by St. Peter, as they collected the precious relics of the blood shed by the first witnesses to the faith in Rome.

As home to thousands of martyrs over hundreds of years, Rome’s claim to the authentic tradition of Christ and the apostles was already strong, but the Counter-Reformation Church made it stronger still. Efforts to excavate, rebuild and decorate the most ancient spaces of the faith formed an argument for the deep roots of a papal Rome sown with the blood of the martyrs that still resonates today for tourists and pilgrims alike.