Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

California’s governor, Jerry Brown (CA-D), called Junípero Serra, the first Hispanic saint of the United States, “one of the innovators and pioneers” in California history. Similarly Bishop Robert McElroy of the Diocese of San Diego called Serra a “foundational figure” of the Golden State.

Not everyone admires Serra, though.

In the lead up to his canonization in September 2015, California state Senator Ricardo Lara proposed removing Serra’s statue from the National Statuary Hall in the US Capitol. Memorials of the 18th-century Franciscan who brought Catholic Christianity to California have been vandalized five times since his canonization—at Monterey, twice in Carmel, in Mission Hills, and most recently at Old Mission Santa Barbara. The front wooden doors and a side wall at Mission Santa Cruz were spray painted in red with the message “Serra St. of Genocide.” Stanford University has a movement to rid the campus of any reference to Serra.

Almost immediately following Pope Francis’ announcement of the canonization in January 2015, many in the media, both Catholic and mainstream, portrayed it as controversial; one is either for Serra or against him. Serra’s story, however, is not so black and white.

When Serra came to California, he was an old man with a single intention—to bring all that he encountered closer to Christ. Toward that end, he learned native languages to better evangelize. He penned what would go down in history as the native bill of rights; yet he was also a man of his time, using self-flagellation as a form of penance and upholding corporal punishment, actions peculiar to us today. He once told the territory’s governor that if the natives should kill him, that they should be forgiven and pardoned.

Read more:

5 Must-see missions on the California Mission Trail

The mission system would continue for another 50 years after Serra’s death in 1784. Author Gregory Orfalea argued in a recent article in The Tidings that it was after Serra that things started to go bad. All one needs to do to realize that Serra was no monster is to read his own words.

Once under secular governance, the missions fell into disrepair and the Mission Indians were neglected. In 1848, Americans began to come in droves and statehood soon followed in 1850. The natives were “in the way” of so-called progress and from there what constitutes as genocide ensued.

The ongoing controversy over Junipero Serra is rooted in our nation’s first “original sin”, the outright genocide of native peoples. Scholar Barry Pritzer estimates that in the early 19th century there were 200,000 California Indians. By the end of the century there were 15,000. It is true that a majority of California Indians who were engaged by missionaries and ultimately converted ended up dying due to exposure to diseases for which they had no immunity, but the near-annihilation of the California Indians came during the Gold Rush, at the hands of the Forty-Niners and with the blessing of the government of California.

Some have charged Serra with complicity in enslavement. According to scholars James Sandos and George Harwood, missions were designed to attract, not destroy. After learning the basics of what it meant to be a Spanish Catholic, the California Mission Indian was required to work like the Spaniard. To leave the mission one had to ask for permission. If one did not return on the prescribed day one was seen as a “deserter.” Gregory Orfalea estimated that 5 to 10 percent did, in fact, abandon the mission.

Read more:

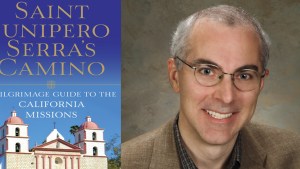

St. Junipero Serra’s Camino: A fast take with author Stephen Binz

Last, a few contend that Serra was unusually cruel. It is true that Serra permitted corporal punishment of “deserters” but only under his own watchful eye. California Polytechnic State University professor emeritus of History Dan Krieger explained that thick whips of cord were used that rarely broke skin. In this case Serra was a man of his time. In the eyes of Spanish society, using physical discipline was a moral act.

Before canonizing Serra, the Catholic Church did its homework. The ecclesial court proceedings to question Serra’s holiness began on December 12, 1948. The evidence brought forth were 2,420 documents (7,500 pages total) of Serra’s writings, 5,000 pages of materials written about him from those who knew him, and testimony of people inspired by his life. A summary of findings would be collected into the Positio (position paper)—Serra’s position was 1,200 pages. The evidence propelled Pope Francis to confidently share in the homily at Serra’s canonization on September 23, 2015 in Washington, D.C., “Junípero sought to defend the dignity of the native community, to protect it from those who had mistreated and abused it.”