In his exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis expresses a constant danger evangelists must keep in mind: “There are times when the faithful, in listening to completely orthodox language, take away something alien to the authentic Gospel of Jesus Christ, because that language is alien to their own way of speaking to and understanding one another. With the holy intent of communicating the truth about God and humanity, we sometimes give them a false god or a human ideal which is not really Christian” (paragraph 41).

This can be seen clearly in some discussion among Catholics when it comes to homosexuality and the gender issues that dominate the news. As statements of fact, it’s hard to find fault with Catholic teaching; the Church is correct to point out that the complementarity of man and woman expresses God’s creative plan for human happiness. Christ reminds us of this plan in the Gospels, and his teaching is unchangeable.

But repeating facts is not the same as being helpful, and often the problem rests in how we repeat the facts of man and woman. Too often our words deal with these topics in the abstract with no regard for the conflicting feelings that some persons may experience.

To paraphrase St. John Bosco, it’s not enough for Christians to love same-sex-attracted persons. It is necessary that same-sex-attracted persons are aware that they are loved by Christians.

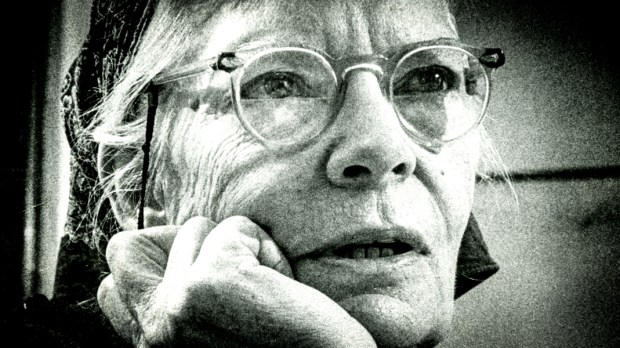

We may find a more constructive approach to accompanying such persons — our brothers and sisters — by looking at the writings of Dorothy Day.

An entry in her diary on September 9, 1975, reveals three reactions to the question of homosexuality which — more than public statements reiterating doctrine — suggest how believers might minister to same-sex-attracted persons.

The diary entry

For Dorothy, homosexuality was not an abstract theory but a personal issue. That is, she realized that it impacted persons on their individual walks with God. As a result, she could only deal with the question on a personal level. In fact, she wrote her diary entry because two female friends came out to her: “I must set down my own insights which came to me after prayer. I only go into this because two of our [friends] have now written and spoken to me of their acceptance of lesbianism.”

Such a personalist mindset should inform all of a Christian’s dealings with people, whatever their issues. Whether clergy and laity, we shouldn’t ask: “How do we deal with this issue?” Instead, we should ask: “How do we respond to our neighbor?”

Dorothy’s reaction to her friends’ news played out in three phases: a feeling of irritation, the search for commonality, and finally the recognition of redemption.

Irritation

Writing about her friends after they had confided in her, Day begins her entry: “I awoke with a heavy sense of a problem nagging at my heart.”

By her own admission, Dorothy could be grumpy. She was in fact quite conservative on matters of sex. She wrote toward the end of the entry that “[o]ne must judge right and wrong and if one considers oneself of the Judeo-Christian faith, one must remember the admonitions in both Old and New Testaments about unbridled sex practiced today in every form and fashion.”

She also echoes a question many traditional Christians have asked themselves: “Why do I have to deal with it, write about it at all?”

Recent attempts to modify the Church’s pastoral approach to homosexuality have tended to minimize the irritation that orthodox Catholics feel at homosexuality’s becoming such a prominent issue in our time. On one level, the attempts at modification make sense. The starting point for this attempted updating is often the pain self-labeled LGBT Christians feel when they face (perceived or actual) rejection by their fellow believers. No doubt this pain is deeply felt, especially when those for whom the Church’s teaching comes easily ignore it.

That said, it’s not wrong to feel irritated — or even angry — when the Church’s teachings are ignored, rejected, and ridiculed. But while our first reaction to the question might be irritation, it cannot be our last reaction.

Commonality

While Day re-articulated for herself the Scripture’s teaching on sexuality, she knew that Christ’s love demands more of her. She writes: “I am always being confronted in mind and conscience with those words of Christ: ‘Do not judge.’”

Convicted by Christ’s words, Dorothy seeks in her diary entry to find common ground with her friends.

She begins by noting that love, as the most powerful force in the universe, must be bridled and directed, lest it run wild: “How great a thing is love, how great a force, a tidal wave, a Niagara, which can utterly destroy, or, harnessed, can supply us with light and warmth and indeed life itself.”

All human love must be shaped by reason and grace. Without the grace of God, Dorothy notes, even the love of man and woman — “natural love” in her words — becomes “delectation in temptation.”

Indeed, the need to perfect our loving makes demands on all of us. Whatever a person’s sexual attractions, the call to conversion in this regard is universal.

Yet Day knew she must go deeper. Christ comes to suffer with us. When a person comes to us in pain, we must go deeper with him or her as well. Day proceeded to do that with a deep and honest examination of conscience for her lesbian friends. She sought to identify with them in their shared humanity. What she comes up with may surprise us. She remembers two intense infatuations that she had with young women — the first the sort of adolescent attraction that is not at all uncommon.

She writes: “I was 15 the first time … I loved her. My own studies became more interesting. I worked harder at my studies. She was in a way a model to me. I never knew her name or anything else about her but in a way she cast a light about her.”

Recall that Dorothy was about 80 years old when she wrote this in the late 1970s. Admitting something like this — even privately in a diary — could not have been easy. Yet she recalls these experiences in order to establish an experiential connection with her friends, putting herself in their shoes so to speak.

Here Day models for us how we might deal with thorny questions surrounding human sexuality, and more importantly with the persons who pose them to us.

- How would I want someone to admonish me for my sins?

- When have I felt unwelcomed by other Christians, and what would I have wanted them to do differently?

- If I don’t want to admit even my private sins, what’s the best way for me to approach someone’s public sins?

As Day exemplifies for us, we should always respond to persons and never just to issues. As a result, the approach we take to big issues, even sexual issues, might change from person to person according to their needs. But no approach will go anywhere until we see ourselves in, or at least establish common ground with, the people we are dealing with.

Before Christ, we are all loved sinners — sinners in different ways perhaps, but sinners nonetheless. We share this with everyone. But Dorothy’s reflection on her two friends moves her even beyond this essential point.

Redemption

Dorothy’s second infatuation with a woman occurred after her conversion to Catholicism. As a result, she interpreted it differently. She writes: “The girl … had a stately beauty, giving an impression of strength. Such strength, I suddenly thought, as the Blessed Mother … How contemplation of that Polish girl deepened my faith, and love for Mary — a real love, a living love which has comforted me.”

Without reading too much into Dorothy’s words — more at least than what she herself admits — we can see in them her understanding of how Christ can transform desire. “Transform” is a loaded term because it could be interpreted to mean that Christ removes wayward desires, homosexual or otherwise. That’s not what happened to Dorothy. Whatever the nature of her attraction — which could have led her to sin — she applied it to the strengthening of her love for the Virgin Mary.

Central to the Gospel is the truth that no part of human life falls outside of Christ’s redemptive work, including the life of the passions. That does not mean Jesus removes every wayward feeling and nagging temptation. As the Lord reminded St. Paul: “Power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9). Christ the Redeemer remains present to us in our temptations, and he calls us back to himself when we sin.

For Dorothy, this truth meant that even as she recalled the Scriptural teaching on human love, she could say without excluding even homosexual temptation: “[O]ne must be grateful for the state of ‘in-love-ness’ which is a preliminary state to the beatific vision, which is indeed a consummation of all we desire.” Because true love is the gateway to glory, even misguided loves — of whatever sort — can be an occasion where Christ, through the transforming power of his cross, can lead us to His Father.

There is a line attributed to G.K. Chesterton: “Every man who knocks on the door of a brothel is looking for God.” Accordingly, we shouldn’t be surprised if our approaching the brothel — or even our experience of homosexual desire — becomes an occasion where Jesus finds us and calls us back to the love that satisfies all longing.

Christian discourse on sexual sin often trends through Dorothy Day’s first two movements. Some believers stop at irritation; others move on to commonality but get stuck there.

Like Dorothy, we take Gospel truth as a given, but we can’t deprive that truth of its power. We should carry that truth through to Dorothy’s third movement and, reflecting on Christ’s redemption, ask ourselves: Where is God present in this person’s woundedness? How do a person’s desires — even sinful ones —occasion God’s work in his or her life?

Dorothy herself writes: “It is this glimpse of Holy Wisdom, Santa Sophia, which makes celibacy possible, which transcends human love.”

As Christ approaches us to heal our wounds, we believers must prepare the way for Him to approach and heal the wounds of others, including — and in a special way — the wounds of our brothers and sisters who experience gender dysphoria or same-sex attraction.