Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

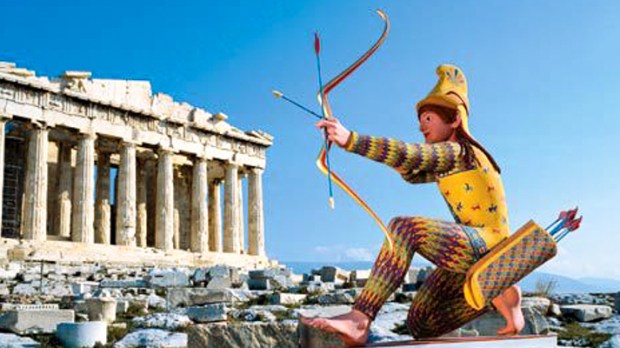

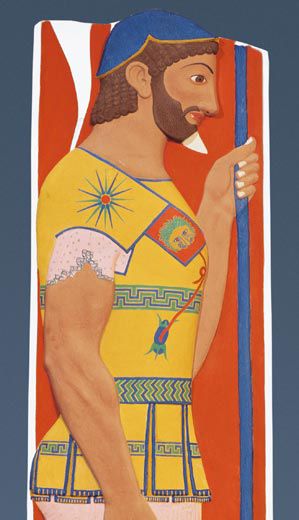

Accustomed as we are to contemplating the whiteness of the marble statues of classical Greco-Roman antiquity, we find it difficult to think that they could ever have had any color. But this was precisely the work of the so-called “kosmetai”: Greek painters who were in charge of applying pigment to bare marble. These kosmetai would give “order” (the Greek word for “order” is cosmos, the opposite of chaos) to something considered unfinished, in need of being delimited. Hence, our “cosmetics.”

Despite the unforgiving passage of time, the remains of pigment in these ancient marbles can be detected using two methods. One involves simply passing an ultraviolet light lamp around the statue. The second, more complex process is the “raking light” method, which reveals, thanks to a certain angle of the illumination on the piece, all the irregularities on its surface, including almost imperceptible remains of pigments.

The German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann has used all these resources over the last 25 years, with the intention of reproducing the colorful past of Greek antiquity. He uses the original resources that the kosmetai had at hand: green pigments obtained from malachite, azure blue, yellow pigments made of different compounds of arsenic, black obtained from the ashes of burned bones.

The result was an exhibition featuring reproductions of classic Greek statues, with the original, startling colors that Brinkmann managed to reconstruct. The show opened at the Glyptothek of Munich in 2003, and then traveled in 2007 to Harvard University. Here, we wanted to share with you some of the images that are part of this exhibition.

To learn more about the Brinkmann project, check the Smithsonian Institute post on the matter, here.