On the night of April 6, 1844, a mob of white Protestant males calling themselves “Native Americans” marched toward a Roman Catholic Church on Brooklyn’s Court Street, intent on burning it to the ground. As they proceeded, their numbers increased to several hundred with shouts of “The church must come down—the church must be gutted—damn the Irish!”

When they arrived, a sizable group of Irish immigrants were waiting to defend it with bludgeons, axes and rifles. But before they came to blows, Brooklyn’s Mayor called out the military and dispersed the crowds.

From the 1830’s through the 1850’s, such scenes were duplicated in nearly every major American city where immigrants gathered in large numbers. But not all ended so peacefully. In Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, convents and churches were burned to the ground. From Kentucky to Maine, riots left Catholic immigrants and Protestant “natives” dead in the street. In short, anti-Catholicism had reached a fever pitch in American life, unseen before and perhaps since.

The principal reason was immigration—mainly from Ireland and Germany—which reached unprecedented proportions during these years. Roman Catholicism, once a despised minority, was now America’s single largest religious denomination. (While all the Protestant denominations combined to outnumber Catholics, the latter outnumbered every individual Protestant church.)

Reaction was fierce. Would America become a mere papal outpost?

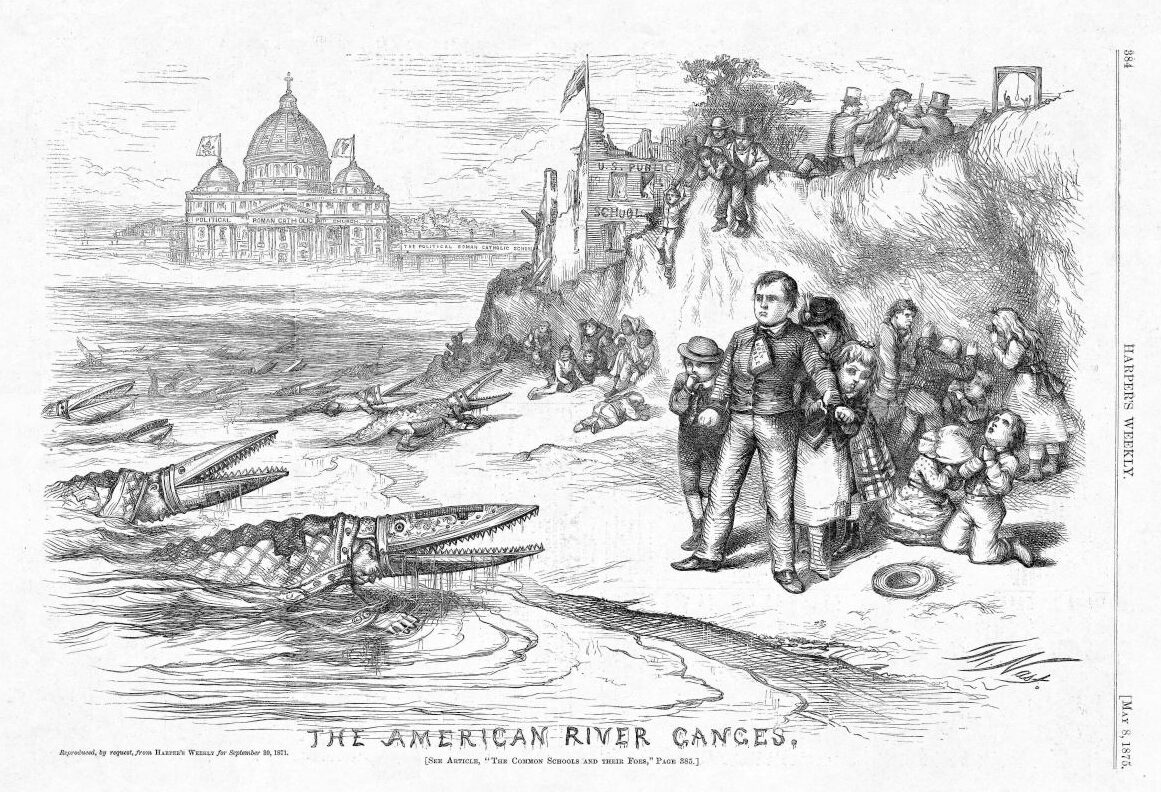

Throughout the country, newspapers with titles like The Protestant, The American Protestant Vindicator, and The Anti-Jesuit dedicated themselves to the cause of “No Popery.” They proposed to defend “Gospel doctrines against Romish corruption.” Debating societies addressed the question, “Is Popery Compatible with Civil Liberty?” Authors like inventor Samuel Morse wrote books warning against Jesuit conspiracies to take over the country.

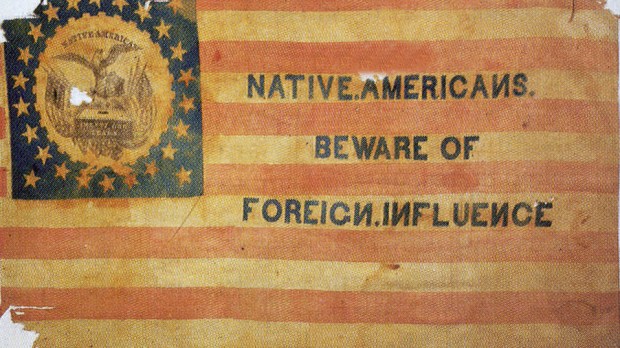

Political parties were even formed, like the American Republicans and the Native Americans. (In the 1800’s, the term “Native American” referred not to the continent’s original peoples, but to native-born Protestants.) In 1835, the Native American Democratic Association won several offices in New York City, pledging themselves to immigration restriction and keeping Catholics out of public life. Over the next two decades, similar parties formed nationwide, but they were confined mainly to the local level.

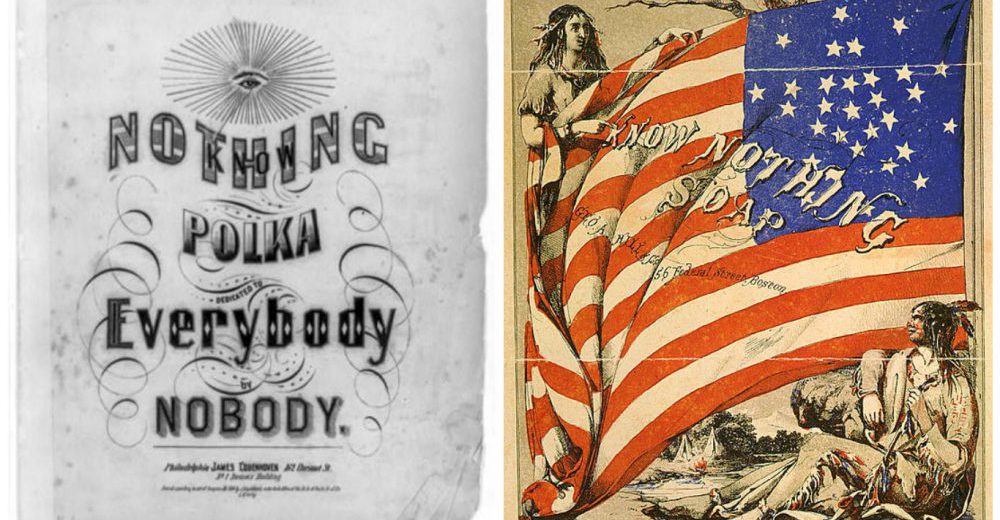

But the most famous and influential of such groups was the American Party, better known as “the Know-Nothings.” It was formed in 1849 by New Yorker Charles B. Allan under the title of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner. Members had to be born in the United States, born to Protestant parents and not married to a Roman Catholic. They had secret handshakes, passwords and signals. Prospective members were asked:

Are you willing to use your influence and vote only for native-born American citizens for all offices of honor, trust or profit in the gifts of the people, the exclusion of all foreigners and Roman Catholics in particular, and without regard to party predilections?

In short, the organization’s purpose was to “resist the insidious policy of the Church of Rome” and to “place in all offices of honor, trust, or profit… not but native-born Protestant citizens.” They were required to keep secret about the group. When asked about it, their response was, “I know nothing.”

Not all anti-Catholics belonged to the Know-Nothing party, but they certainly supported it wholeheartedly. In the 1852 elections, the Know-Nothings captured major offices in several American cities. Their high tide came in 1854, when they garnered control of several states on the eastern seaboard. In Massachusetts, they elected seventy-five congressmen, a governor, and all the state officers, and the entire state senate.

By then, historian Ray Allan Billington writes, the Know-Nothings became “the rage of the day.” Items with the Know-Nothing label included candy, soap and toothpicks. Stagecoaches and clipper ships were named for it. Members looked forward to the 1856 presidential elections, when they hoped to sweep their candidate into the White House.

Catholics worried over the possibility of an anti-Catholic president. By 1856, however, other issues overshadowed anti-Catholicism. As the country divided over the issues of slavery and national union, and with the rise of a new Republican Party, the Know-Nothing platform took a backseat to the larger questions of the day.

As the country advanced toward Civil War, the Know-Nothings faded into the background. With Catholic immigrants shedding their blood in defense of the Union, it seemed ludicrous to question their patriotism.

Read more: Feinstein and Durbin: Very models of a modern move to Know-Nothing?

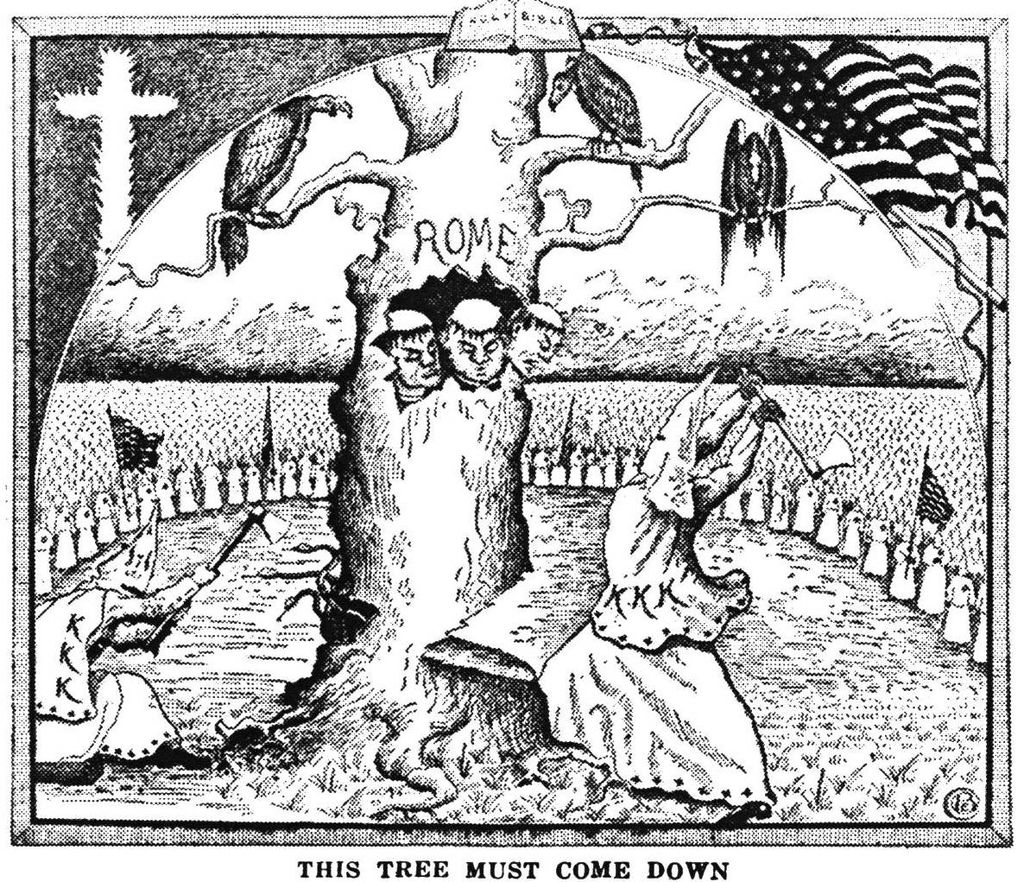

But the group’s demise didn’t mean the end of anti-Catholicism, which historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. calls the longest reigning prejudice in American history. In decades to come, other anti-Catholic groups would gain ground, including the Ku Klu Klan in the 1920’s. But none would gain the influence or the numbers that the Know-Nothings had for a brief time in the 1850’s.

Originally published online in 2011. Reprinted here by agreement with the author.