Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

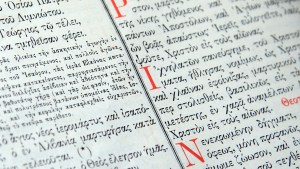

The compilation of the Bible as we know it today was a long, drawn-out process. It started with oral history that was passed on to each generation and then this history was written down by inspired authors and brought together to form various “books.”

Then during the 4th century AD the need arose to officially codify the Bible, which by this point was already starting to come together. The approval of which books to include started with the Council of Laodicea in 363, was continued when Pope Damasus I commissioned St. Jerome to translate the Scriptures into Latin in 382, and was settled definitely during the Synods of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397).

The goal of this process was to dismiss all erroneous works that were circulating and to instruct the local Churches which books could be read at Mass.

Read more:

Where did the Bible come from?

The Church firmly believes that the Holy Spirit was guiding this process and continues to accept all those books that were approved at these councils.

However, when Martin Luther approached the Bible he saw an apparent discrepancy. He noticed how certain books from the Christian Old Testament were not the same as the Hebrew Bible that was generally accepted by European Jews. Luther thought that meant Jesus was not familiar with these texts and they were not inspired by God and only added on by the Church. These texts included Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, I and II Maccabees and sections of Esther and Daniel.

These books became known in Protestant circles as the “apocrypha” and were eventually omitted from every Protestant Bible. This is evident when browsing the shelf of Bible versions, as some will say “includes apocrypha.”

In reality the Hebrew canon of scripture that Luther was referring to was not developed until the 2nd century. Before that there was debate among Hebrew scholars, but most Greek-speaking Jews of the 1st century preferred the listing of books in the Septuagint translation. This translation was developed about 200 years before the birth of Jesus and was widely accepted as a legitimate translation. Tradition relates how King Ptolemy II of Egypt ordered a translation and invited Jewish elders from Jerusalem to prepare the Greek text. Seventy-two elders, six from each of the 12 tribes, arrived in Egypt to fulfill the request. The Septuagint included all the books of the Old Testament, including those that Protestants currently refer to as the apocrypha.

When the apostles when out to evangelize the Greeks they used the Septuagint because of its wide acceptance as an inspired translation. This is clearly evident in the New Testament where “[t]wo thirds of the Old Testament quotations in the New are from the Septuagint.” The writers of the New Testament even referred to passages from the apocrypha, such as Hebrews 11. As a result, the early Church quickly adopted the Septuagint.

The main issue behind this all is the recognition that the Holy Spirit guides the Church in matters of faith and morals. So when the Church approved the official canon of Scripture, she did so with the help of God. While it is true that the inclusion of the apocrypha was primarily based on the historical reality of the early Church, the primary force behind it was the Holy Spirit.