Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

By now we’ve all heard about the notorious “Google manifesto,” a 10-page email memo that got Google engineer James Damore fired from his job. Social media went into overdrive when it got wind of the internal memo, producing copious responses of increasing vehemence until the engineer was doxxed, reprimanded, and fired.

Read more:

Men’s and women’s brains are different — literally

The memo itself, titled “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber,” is an analysis of Google’s diversity initiatives, which have ramped up in the wake of a wage discrimination investigation by the US Department of Labor. In it, Damore lays out biological differences between men and women, arguing that women are underrepresented in tech not because of bias or discrimination, but because of inherent psychological differences. He begins with this disclaimer:

“I’m simply stating that the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women differ in part due to biological causes and that these differences may explain why we don’t see equal representation of women in tech and leadership. Many of these differences are small and there’s significant overlap between men and women, so you can’t say anything about an individual given these population level distributions.”

That sounds reasonable. I wrote something similar myself last week about the biological differences between the sexes; but I also wrote about the need to treat each person as an individual rather than as a predetermined extension of those differences. Damore, unfortunately, takes biological differences and uses them precisely as determiners, extrapolating from them in order to explain individual traits which he then applies to women — and men — in broad, sweeping brushstrokes. This is backwards.

To take an example, he begins with the assertion that women tend to be more interested in people, men in things. Even critics of his memo have acknowledged that this is uncontroversial — it’s widely acknowledged as scientific fact. The problem here isn’t the science: it’s the application. Damore suggests that because women are more people-oriented, Google should encourage more collaboration. But he cautions that there are limits to how certain people-oriented roles can be, and Google can’t deceive itself or its employees about that. Then he adds this aside: “(some of our programs to get female students into coding might be doing this).”

Read more:

The greatest sex scandal may be the drive to abolish male and female

It’s one thing to acknowledge differences in men and women, or even to claim that they help contribute to a gender gap in STEM, and the idea that a company should be forced to have dead-even representation of men and women is ridiculous. Damore and I agree on that.

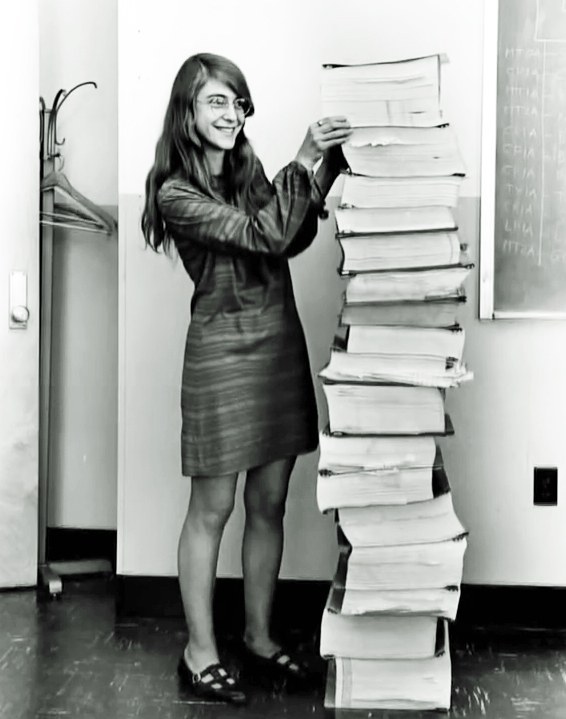

But to go beyond the hypothetical and suggest that encouraging women to learn coding might be deceiving them is wrong, and as a consequence Damore ignores some pertinent scientific evidence. Behold Exhibit A:

Of course, taking the existence or the accomplishments of Margaret Hamilton (or Ada Lovelace, arguably the first programmer) and then expecting, much less demanding, that women make up half of all coders is equally absurd.

But the problem here is not rocket science (or even computer science). That women tend to be more people-oriented or that men tend to be more thing-oriented is just that, a tendency. They are not universal rule. This is a fundamental problem not just with the memo, but also with the diversity demands that apparently prompted it — men and women are being put into rigid boxes labeled “male” or “female” rather than being allowed to contribute their unique, individual talents and skills to the company.

And that’s the real story here: the problem isn’t the memo at all (because the memo is just Damore’s opinion), it’s the response to it. When we as a society choose to respond to ideas we disagree with by doxxing and silencing, we’re not responding to the person but to the position, and that overlooks the individual just as much as sweeping generalizations do.