As a whole, the Catholic Church was slow to get fully involved in the Civil Rights movement of the mid-20th century. Whether or not Catholics publicly endorsed segregation, they certainly accepted it in their churches and schools, North and South.

Many Catholic institutions weren’t fully integrated until the 1960s, but before that era there were some exceptions to that general reality, usually forged via an informal network of laypeople, priests, and nuns who were long-committed to promoting racial justice.

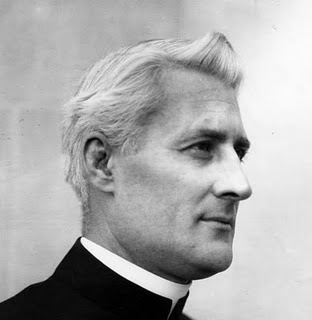

One of these priests was a Midwestern Jesuit who led sit-ins, marches, and boycotts long before they made national headlines. Tall and handsome, John Markoe looked like a movie star, and in fact his story would actually make a good movie; it is the story of a lumberjack, football star, soldier, alcoholic, priest, teacher, activist. Markoe’s biography, a peer noted, “reads like fiction.” NAACP leader Roy Wilkins said Markoe “fought the Civil Rights battle long before it became respectable, or even popular.”

Born in 1890 to a blueblood family whose ancestors included Benjamin Franklin, John Prince Markoe was the son of a prominent Minnesota doctor. At 18 he was accepted to West Point, but deferred the appointment in order to go west, to work on the railroads. In 1910, he entered the military academy, where his friends included Dwight Eisenhower. He played football against Knute Rockne and Jim Thorpe, and was named an honorably-mentioned All-American.

When he graduated in 1914, the yearbook said: “Possessing unlimited abilities, there is very little which he is incapable of performing.” But he earned his classmates’ contempt when he stood up for Marcus Alexander, the Point’s only African-American cadet. His final class ranking might have been higher, had Markoe not been a full-fledged alcoholic by his senior year.

Lieutenant Markoe was assigned to the Tenth Cavalry, a Black regiment. He welcomed the opportunity, fraternizing with his troops more than was deemed appropriate for a white officer. But nine months after graduation, heavy drinking cost him his commission. He never fully forgave himself. Back in Minnesota, he entered the lumber business and enlisted in the National Guard.

In 1916, during the unofficial war against Pancho Villa in Mexico, he regained his commission. Down in Mexico, Markoe got letters from his brother Bill, a Jesuit working with African-Americans. These piqued his interest, and he started thinking about another kind of life than the army. After his discharge in 1917, Captain John Markoe joined the Jesuits in Missouri. He and Bill took a private vow to work for the “salvation of the Negroes in the United States.” (Bill later worked with their cousin John LaFarge, also a Jesuit, for racial justice.)

As part of his training, John was assigned to St. Louis, a highly segregated city. African-American Catholics were relegated to separate parishes, denied a Catholic education, and banned from Catholic hospitals. (The local archbishop was notoriously racist.) John worked in Black parishes and attended NAACP meetings. In magazine articles, he argued that racism was a moral issue, even a heresy. His work was not well-received by local whites, Catholics included.

Ordained in 1928, Markoe was assigned to St. Elizabeth’s Church, a Black parish in St. Louis. The work was hard, yielded few results, and some of his fellow priests ostracized him. It took a toll, and after 20 years of sobriety, he returned to the bottle. On one occasion, it took half a dozen police to drag the priest out of a bar, as he had taken on its entire clientele. For seven years after that, he stayed at St. Joseph’s Infirmary, Missouri, fighting alcoholism.

In 1943, he re-entered the fight. Assigned to St. Malachy’s, another Black parish in St. Louis, Markoe and his brother Bill campaigned to desegregate the Jesuits’ St. Louis University. Father Claude Heithaus, a sociology professor, publicly asked why the school admitted people of all faiths, but rejected Catholics on account of their color. They won the fight, but John was soon sent (“exiled,” some said) to Creighton University, Omaha, where he spent the rest of his days.

Initially it seemed like his Civil Rights days were finished, but they were really just beginning. Omaha, where segregation was still the rule, had a NAACP chapter as early as 1912, and in 1919 it witnessed a race riot. Malcolm X was born there, but Klan activity forced his family’s departure. Whitney Young, director of the National Urban League, worked there in the postwar years.

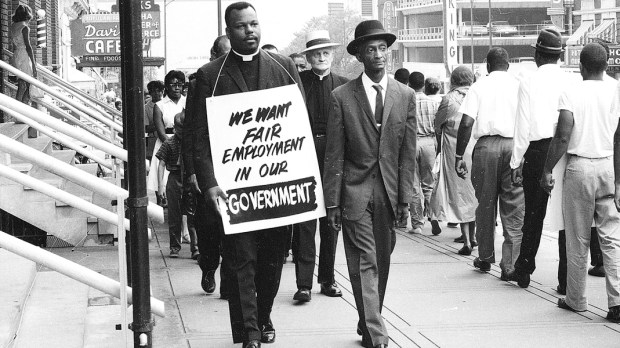

Markoe’s official assignment was teaching math, but he worked mainly with the DePorres Club (named for St. Martin DePorres, a saint of African descent), which he organized to educate the public on race. A decade before these issues attracted national attention, the club led sit-ins at Omaha restaurants, boycotted companies with discrimination practices, and organized public marches. Markoe was there at every step. One member said, he “kept us going.”

“Cap” (an army nickname) often said, “Racism is a God-damned thing. And that’s two words: God-damned.” When a Black veteran encountered opposition occupying his new home, Markoe and Whitney Young sat on the stoop for neighbors to see, while DePorres Club members moved the family in. John Howard Griffin, author of the controversial 1961 book Black Like Me, said Markoe was “in the cauldron when most of us were in diapers.”

By the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing, and Markoe was a revered figure among Jesuits. He was slowing down, but even in old age, he had many visitors. One priest noted: “They come from the ghetto most mornings: the poor, the alcoholics, the mentally depressed. Cap offers them what encouragement he can.” As race riots swept America in 1967, the dying priest told fellow Jesuits never to “give an inch.”

At Markoe’s funeral Mass, Father Henri Renard, the homilist (and close friend), called him a fearless character who fought for the “the poor and oppressed.” John Markoe is one of the unsung heroes of the Civil Rights movement, which is how he wanted it. Unassuming and modest, during his 50 years working with the African-American community, he never sought attention for himself. Like St. Ignatius Loyola, another ex-soldier turned priest, he embodied the Jesuit ideal of “men for others.”

First published online in 2012. Reprinted with kind permission of the author.