What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think about someone who’s a perfectionist? Is it someone with an immaculate house, or a high-powered job? Someone obsessively into working out, or a top specialist in their field? Whatever comes to mind, you probably think of it (as I did) in terms of success. Most of us associate perfectionism with achievement.

Read more:

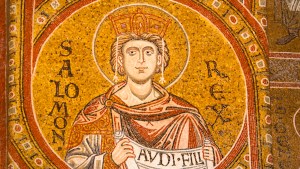

What King Solomon’s example teaches us about real ‘success’

But the opposite is true according to three clinical psychologists — perfectionism actually impedes success. These psychologists researched perfectionism over the last three decades and have written a book about it, aptly titled Perfectionism. As they explained to Thrive Global, the disconnect is because true perfectionism is not directed outward, but inward.

As they understand it, perfectionism isn’t about perfecting things: your job, a specific project, the way you look, or a relationship. At a fundamental level, it’s about perfecting the self, and this urge doesn’t come from a healthy place: “All components and dimensions of perfectionism ultimately involve attempts to perfect an imperfect self,” the authors write.

The article details what the researchers have found about the evolution of perfectionism, particularly how it is rooted in a child’s attachment style and gets passed from one generation to the next. The researchers also conclude that cognitive behavioral therapy is of limited use in patients with perfectionism, and psychotherapy is more useful to help them change their relationship with themselves.

Read more:

Are you a perfectionist? End each day in peace with this prayer

Paul Hewitt, one of the psychologists behind the research, told Thrive Global that shifting the internal narrative his perfectionist patients have with themselves is a main goal in therapy. He explains that this internal narrative is indicative of the relationship they have with themselves, and that the harshness of that relationship can be “breathtaking,” on par with a “nasty adult beating the crap out of a tiny child.”

But changing that internal narrative must be a herculean task if the patient’s external interactions seem to confirm what they believe about themselves. If their lives have been measured by their loved ones in terms of success or failure, and no one has cared enough to understand why they struggle and what they fear, how can they be expected to do the same?

What I find fascinating is the potential effect this understanding of perfectionism could have on our social dynamic if it were widely recognized and embraced. What if, instead of seeing a teenager who struggles with procrastination and anxiety as lazy and too high-strung, her parents saw her as struggling against feelings of self-hatred and despair? How would their response to her, and their relationship with her, change? How would she change?

Read more:

5 Ways to make downtime when you’re completely swamped

Likewise, how would this understanding of perfectionism as a relationship with the self impact those who struggle with it? As a society, we talk a lot about “self-care” and often boldly proclaim the need to “treat yourself.” But if we could shift our understanding of “treating” ourselves away from indulgence and toward a truer form of self-compassion, wouldn’t we begin to develop into freer, stronger, less fearful human beings?

On the micro level, shifting our relationships with ourselves could indeed free individuals from perfectionism. But on the macro level, this shift could have a cascade effect that frees more of us collectively from the brittleness and fear that has become endemic. And it all comes down to one thing: compassion. For ourselves, and each other.