When I was 20, I went through the University of Dallas’s Rome Program, one feature of which is called “10-day,” a week and a half toward the end of the semester when students use their Eurorail pass (or brave Ryan air) to travel anywhere they want. The only requirement, other than the students being back in time for class 10 days later, is that students have to leave for 10 days — no hanging out in the shelter of the familiar.

I had planned to visit Paris, Berlin, and Copenhagen with one of my roommates before meeting up with our other roommate in Amsterdam at the end of our trip. By that time I had become familiar enough with the train system that everything seemed to go swimmingly, until we stepped off the train in Paris and headed for the metro — where it became immediately and abundantly clear that I couldn’t read a map.

Read more:

Why you need to stop saying “I’m too old for that”

Luckily for me, my roommate could. She managed to navigate us through Europe with only one major snafu. But now I look back in horror and think, what would have happened if neither of us could read a map?

Being able to navigate is one of the life skills former Stanford dean Julie Lythcott-Haims recently told Quartz magazine that every 18-year-old should have. She lists 8 life skills in total, and while navigation certainly resonates with me, this one is my favorite:

An 18-year-old must be able to take risksThe crutch: We’ve laid out their entire path for them and have avoided all pitfalls or prevented all stumbles for them; thus, kids don’t develop the wise understanding that success comes only after trying and failing and trying again (a.k.a. “grit”) or the thick skin (a.k.a. “resilience”) that comes from coping when things have gone wrong.

Lythcott-Haims is the author of NYT bestseller How to Raise an Adult, and you can tell from her list that she knows what she’s talking about. It’s full of practical, essential skills that are often overlooked when we think about how to prepare our kids for college and life, things like knowing how to talk to strangers or contributing to the running of a household.

This last one, though, struck me because it’s so hard. And by that I mean hard for us, not for them. We don’t want to see our kids hurt, and failure hurts. We all know this from experience. Yet somehow, letting our kids feel the pain of failure (especially if we can see it coming) feels like a betrayal. It feels antithetical to our role as parents, since we spend so many early years nurturing and protecting.

Read more:

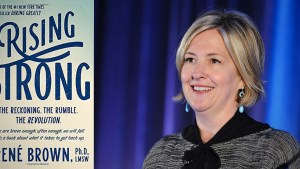

Brené Brown’s ‘Rising Strong’: Forging wisdom from failure

I’ve said that I’d never let my kids try a 10-day in college, because what if what could have been for me comes true for them? What if they get lost, or mugged? What if they make a poor decision, choose the wrong stop, and get stranded outside an airport in a blizzard? What if they need help and can’t find it?

That one major snafu on our 10-day happened at the end, when we missed our flight back to Rome because we got off the train at the wrong stop. The airport in Brussels wouldn’t let us spend the night inside, so we huddled against the building instead, trying to stay out of the snow. The only thing we had to eat was a backpack full of Cadbury chocolates that my roommate had gotten in London.

As a parent, this story is terrifying. But it’s one of my favorite memories. We made it back to Rome cold, tired, sick of Cadbury, but alive and newly aware of our own resilience (and of the importance of navigational skills).

Ironically, protecting our kids from the pain of failure is itself a failure. It’s failing to let them experience the life we know is coming at them, the life we can’t protect them from forever.

It’s failing to let them learn that failing at something does not make them a failure — it makes them human. And like all humans, they only have two choices: give up, or try again.

If they don’t learn that at home, when they have support and encouragement to make the right choice, how can we expect them to make it when they’re on their own? If we don’t let them fail, they might not ever know what they are capable of. They might go through life dependent on the help of others, unable to navigate both literally and figuratively.

In the end, the idea of my children being incapable of handling whatever adventures and misfortunes come their way on a 10-day jaunt through Europe is more frighting than the idea of the adventures and misfortunes themselves. If I’ve done my job well, they’ll come back stronger than ever and with ridiculous stories to tell — just like I did.