When I first read The Lord of the Rings seriesby J.R.R. Tolkien, I wasn’t looking for a love story. After all, I was in second grade and ready to read about the adventures of hobbits, dwarves, and elves. I was content with stories of traveling, sword fights and good versus evil. Frankly, I could have done without that “love stuff.” But as I continued to revisit the books as I grew older, I discovered that, intermingled with stories of dragons and magical rings, Tolkien wove an incredible story of authentic love.

Read more:

Interview with JRR Tolkien in 1968 and Adam Tolkien in 2007

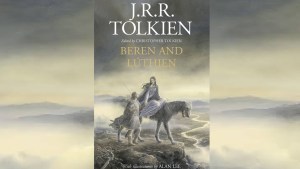

When I was in college, I had a new appreciation for the story of Aragorn and Arwen, whose love conquered seemingly impossible and daunting obstacles. But before Aragorn and Arwen’s romantic and inspiring story was the story of Beren and Lúthien, ancestors of Aragorn and Arwen who lived in the First Age of Middle Earth. For years, the love story of Beren and Lúthien remained incomplete until Tolkien’s son, Christopher, compiled and edited pieces of the story into a final product. Over two decades after Tolkien’s death, his book Beren and Lúthienwas finally released in June, and readers are discovering how close the romantic story was to Tolkien’s heart. Before Tolkien penned the inspiring love story of Beren and Lúthien, there were John and Edith.

As teenagers, John and Edith fell head over heels in love with each other. They adventured out in the countryside and were sure that they were made for each other. But after his school grades slipped, John was told he would no longer be able to stay in touch with Edith. They drifted apart, but John never forgot Edith. After finding out that Edith was engaged to marry another man, John rushed home to declare his love for the woman of his dreams.

Does this story sound like a fairy tale? It’s actually the love life of J.R.R. Tolkien, who created Middle Earth, and the tale that inspired the romance found in TheLord of the Rings series. Without a doubt, the origins for the tales of romantic love and ultimate sacrifice were inspired by Tolkien’s deep love for Edith Bratt.

Years after I rolled my eyes through the romance of The Lord of the Rings as a second grader, John and Edith’s story resonated in my romantic heart, especially since I recently entered married life myself. Tolkien expertly writes about the reality of marriage in a poignant, striking tone: “Nearly all marriages, even happy ones, are mistakes in the sense that almost certainly … both partners might [have] found more suitable mates. But the real soul-mate is the one you are actually married to.” Marriage is not all roses, and Tolkien also acknowledged that love is a deliberate decision that spouses choose, especially on the days when the emotional feelings have faded: “No man, however truly he loved his betrothed and bride as a young man, has lived faithful to her as a wife in mind and body without deliberate conscious exercise of the will, without self-denial.”

Read more:

What C.S. Lewis can teach us about true love

When Tolkien submitted the story of The Lord of the Rings series to a publisher, he was told to remove the romantic parts of the plot. His publisher didn’t think that readers of daring adventure and magic needed the added drama of love. Tolkien couldn’t disagree more. “He thinks Aragorn and Arwen are unnecessary and perfunctory,” Tolkien wrote in a letter to Rayner Unwin. “I hope the fragment of the ‘saga’ will cure him. I still find it poignant: an allegory of naked hope. I hope you do.” Tolkien’s love story stayed as an integral part of Middle Earth. But Tolkien’s passion for authentic love is not just for stories — his love with Edith teaches the beauty and importance of persevering patience, communication, and mutual interests in a romantic relationship.

Tolkien was the young age of 16 when he met and fell in love with Edith, who was three years older than he was. Because John’s parents had died by the time he was 12, Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan became his legal guardian. The priest was not pleased with Tolkien’s romantic interest, since Edith was an Anglican. He ordered Tolkien to stop all contact with her until Tolkien turned 21. Tolkien obeyed his guardian’s wishes, and spent the next five years patiently waiting for the day he could once again declare his love.

In a letter to his son, Michael, Tolkien opened up about the struggle of those five years, writing: “I had to choose between disobeying and grieving (or deceiving) a guardian who had been a father to me, more than most fathers … and ‘dropping’ the love-affair until I was 21. I don’t regret my decision, though it was very hard on my lover. But it was not my fault. She was completely free and under no vow to me, and I should have had no just complaint (except according to the unreal romantic code) if she had got married to someone else. For very nearly three years I did not see or write to my lover. It was extremely hard, especially at first. The effects were not wholly good: I fell back into folly and slackness and misspent a good deal of my first year at college.”

Read more:

Tolkien’s greatest mythological work now available in a single volume

On the night of his 21st birthday, he met his love underneath a railroad bridge and told her of his enduring love and desire to spend the rest of his life with her as his bride. She returned the engagement ring offered by another suitor, converted to Catholicism and announced her engagement to Tolkien.

Edith not only became Tolkien’s wife, but also his muse. In a letter to his son, Tolkien spoke of how Edith inspired him, writing: “I never called Edith Luthien – but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks at Roos in Yorkshire (where I was for a brief time in command of an outpost of the Humber Garrison in 1917, and she was able to live with me for a while). In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing – and dance.”

Tolkien’s biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, wrote that the couple’s marriage was characterized by a deep love. “Those friends who knew Ronald and Edith Tolkien over the years never doubted that there was deep affection between them. It was visible in the small things, the almost absurd degree in which each worried about the other’s health, and the care in which they chose and wrapped each other’s birthday presents’; and in the large matters, the way in which Ronald willingly abandoned such a large part of his life in retirement to give Edith the last years in Bournemouth that he felt she deserved, and the degree in which she showed pride in his fame as an author.”

Read more:

Was the world of Tolkien’s ‘Lord of the Rings’ based on a kingdom in East Africa?

The story of Beren and Lúthien became so close to John’s heart that when Edith passed away in 1971, John had “Lúthien” engraved on her tombstone. The author’s tombstone would later read “Beren” when he died a short two years later in 1973. When he explained his choice in the engraving, Tolkien said, “She was (and knew she was) my Luthien. I will say no more now… For ever (especially when alone) we still met in the woodland glade and went hand in hand many times to escape the shadow of imminent death before our last parting.”

For years, the love story of Beren and Lúthien remained incomplete but now, thanks to their son and over two decades after Tolkien’s death, Beren and Lúthienis here and readers are discovering how close the romantic story was to Tolkien’s heart. Without a doubt, the origins for the tales of romantic love and ultimate sacrifice were inspired by his deep love for Edith.

A skilled writer and editor, Christopher Tolkien follows in the footsteps of his father. He has finalized many of his father’s early works including The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The History of Middle Earth and The Children of Húrin. In the preface of Beren and Lúthien, Christopher writes, “In my ninety-third year this is (presumptively) my last book in the long series of editions of my father’s writings. This tale is chosen in memoriam because of its deeply-rooted presence in his life.”