Pope Francis the other day said that in a sense, every Christian is called to be a martyr. For a lot of us, that might be the last thing we’re ready for. Which is why the Church in her wisdom marks the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul and the early Church martyrs around this time of year every year.

And, in the U.S., it happens to be at a time when the secular calendar also focuses on freedom.

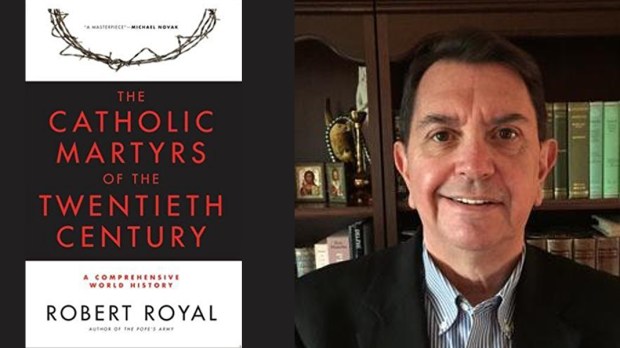

A few years ago, Robert Royal wrote The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century: A Comprehensive World History, and that it is. He talks about the witness of the martyrs and our Christian lives today.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: You write, “It is worth noting that martyrs are real human beings, human beings like ourselves who were fearful when they were placed in extraordinary circumstances and yet managed to act in extraordinary ways.” Why is this important to point out?

Robert Royal: When I did the research for my book, I was struck by the fact that the people who ended up as martyrs — often dying quietly and even praying for their killers — were not the plaster-saint types we read about as children in books about saints. In fact, with rare exceptions, it’s only when they were put to the test that what they were made of showed itself. None of us can know how we’d react if we were told to apostatize or die. I’m confident the recent martyrs in the Middle East and North Africa didn’t expect to be questioned that way. But they were and are. Surprisingly, there are few who abandon faith in those moments. A reality you wouldn’t predict, and worth contemplating.

Lopez: You write that martyrdom is in a deep sense the paradigm for the Christian life. “Any person who starts to follow the Master seriously cannot help but find himself or herself attacked by the same forces that attacked him.” Then who on earth would ever want to be Christian, and how does a “willingness to die” liberate?

Royal: The German philosopher Hegel describes the way that a slave becomes free. He says, suppose there’s a master and a slave, and like most slaves, the slave is threatened or beaten, and therefore daily submits to the will of the master. But say a day comes when the slave has had enough. He decides — and says to the master — “I’m through. Do whatever you want to me, but I’m not being a slave anymore.” At that point, the master has no further power over the person who was once a slave.

You might say that something similar happens when someone is willing to embrace martyrdom. You can’t explain why God’s Providence puts good people in harm’s way. But maybe it has something to do with manifesting this ultimate freedom. I don’t know.

A woman asked me once after I’d given a lecture on the 20th-century martyrs if I hadn’t been depressed researching and writing that book. The question stunned me. That question had never crossed my mind. In fact, I thought spontaneously: I’ve never spent so much time with such obviously unselfish people.

Lopez: What should every young man know about Miguel Pro?

Royal: Out of all the figures from the 20th century that I studied, Pro may be my favorite. He was a real cutup — loved plays and practical jokes, which enabled him to survive for a while when he was working as a priest during the crackdown in Mexico. (He’d studied at the Jesuit seminary in Los Gatos, California; one fellow seminarian said that if you’d asked him who was likely to become a saint/martyr from their class, Pro would have been very far down the list.)

Read more:

Photos of this priest’s martyrdom were meant to dissuade Catholics; that’s not what happened

My favorite story about him — maybe one of the most amusing stories, if you can put it that way, in all Christian martyrdom — is when he showed up at a Communion “station” at a private home (all the churches in Mexico were closed at the time). Two plainclothes policemen were outside. Pro’s superiors had warned him not to risk his life needlessly, people needed him. But people also needed to have a regular expectation that priests would show up for Confession and Communion. Pro went into one of his many impersonations, this time pretending he was a lieutenant of the detectives. He quickly flipped the lapel of his suit jacket as if there was a lieutenant’s badge there: in reality there was nothing.

“What’s going on here, men?”

“We think there may be a priest inside.”

“Wait here while I check.”

Pro goes in, distributes Communion, and walks out again.

Men: “Well, Sir?”

Pro: “False alarm. Stand down.”

This was, of course, the same brave man who President Calles thought would break down and deny his Faith in front of a firing squad. Calles invited the media of the world to witness it. Instead, photos of Pro with his arms outstretched, praying “Viva Cristo Rey!” embarrassed the Mexican government around the world.

Lopez: What is underappreciated or forgotten or not known about Oscar Romero?

Royal: I confess that for me personally Archbishop Romero was a hard case to understand properly. I was involved in the turmoil in Central America in the 1980s and it wasn’t the best way to learn fairness to all concerned. But as I looked carefully into Romero, I found he wasn’t easy to pigeonhole. He looked like a liberationist at the time. In fact, shortly before he died he was on retreat, with Opus Dei of all groups. And if you look at the whole body of his writings and homilies in the period of Salvador’s worst troubles, they’re remarkably balanced and non-ideological. That alone shows heroism of a rare sort. Whether he was a martyr and saint — that’s for others to decide, of course. But he was a more noteworthy figure than was evident at the time — at least to me.

Lopez: If you had it in your power to make sure every Catholic knew two 20th-century martyrs’ stories, who would they be?

Royal: Pro and Stein would have to be high on the list, but there are so many more — victims of Communism, Nazism, anti-clericalism (3,000+ in Spain alone during the Spanish Civil War). It’s like asking a parent which are the two favorite children. I’d advise anyone with an interest in the subject simply to wade in. There’s a whole history there and without it our knowledge of the 20th century is woefully incomplete.

Lopez:What is “the Catholic thing”? Why is it important?

Royal: Well, besides being the title of the daily column series that I edit, I’d say the “Catholic thing” is the vast and rich body of spiritual teaching, art, architecture, music, literature, educational institutions, hospitals, relief agencies, social teaching, daily support, global church network, and much more that’s 2,000 years old, and counting. Even longer if you count the Jewish roots that are integral to Catholicism. I think of it as unique because there’s nothing else like it in the world. Even if you aren’t Catholic or dislike Catholicism, it’s a massive cultural reality worth knowing.