Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

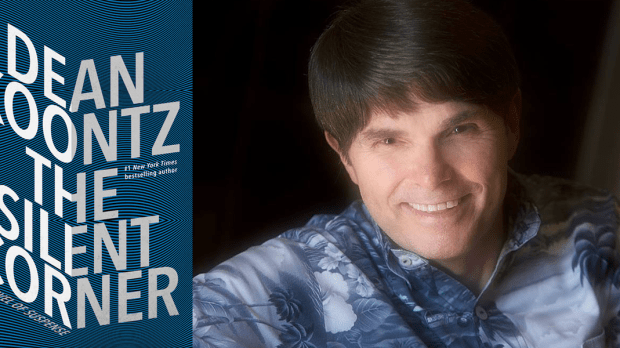

More and more of the Catholic world has been paying attention to Dean Koontz, the popular fiction writer whose books are known for their heart-pounding action scenes and often become New York Times bestsellers.

Koontz, who rarely does any kind of press, has given two hour-long interviews to EWTN and has been featured in the National Catholic Register, wherein he discussed his deep Catholic faith. The author was well into his 8-book Odd Thomas series at that point, and when it wrapped up with the aptly-titled Saint Odd in early 2015, many Koontz fans christened the franchise his best achievement thus far.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the original Odd Thomas (2003) stands as something more than a popular novel. Its clever literary sleight-of-hand, coupled with its masterful re-presentation of the distinctive truths of the Catholic faith in a modern mythos, makes it a book worth reading several times and even studying in groups. Koontz has written many books since then—Innocence (2013) and The City (2014) standouts among them—but none has quite compared to the alluring art of the original Odd Thomas.

Koontz tried something different with late 2015’s Ashley Bell: a high-stakes murder mystery featuring an uncredentialed but feisty heroine who must piece together her shattered world. Its modern detective work was reminiscent of Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series but without the casual sex and with a more firmly grounded sense of ethics.

Ashley Bell set the stage, however, for Koontz’s latest: The Silent Corner, which is subtitled A Novel of Suspense but is in fact a thriller in the military/spy tradition. It is Koontz’s best work in nearly 15 years. The fiery protagonist Jane Hawk is a special unit FBI agent, which gives her all the skills and credibility Koontz needs to pull off a novel of dark espionage. As is de rigueur for the genre, the book’s central conflict revolves around a mysterious technology that, if misused, could threaten the future of humanity itself.

Fans of the great writers in this genre—Vince Flynn (also a devout Catholic), Brad Thor, Daniel Silva, and others—know that these kinds of titles have only become more popular in the past decade. In terms of conventions, readers have come to expect a certain “geek out” factor from these books: exquisitely detailed descriptions of weapons, ammunition, and gear; precisely delineated movements of each person involved in the scenes of tactical combat; and downright garrulous characters who discuss the tortuous ins and outs of complex strategic maneuvers. Contemporary thrillers are also gritty, with graphic descriptions of kill shots, wince-worthy injuries, and all-too-real portrayals of torture.

Leave it to Koontz, one of the masters of modern horror, to give us something even scarier. Most military thrillers focus primarily on terrorism as we know it, which is frightening enough: biological warfare, suicide bombers, and the like. In The Silent Corner, Koontz has given us a terrifying vision of ideological terrorism that ends in most of humanity’s forced submission in slavery to a ruling elite—a fate worse than death.

As might be expected, Koontz tones down the level of “geek chic” the hard-boiled military thriller fan might want. That’s not to say it’s not there. On the contrary, one of the most joyfully destructive scenes in the book involves a half-million dollar SUV/tank hybrid driven by the good guys, and Koontz takes his time to explain in narrative terms exactly why such an exotic vehicle is necessary for the job. Other weapons choices—from concealed guns to hidden devices—receive similarly analytical treatment.

I won’t reveal the novel’s main technological villain here, but I will say that Koontz has covered similar ground in the past, particularly in his 77 Shadow Street (2011). That novel suffered from a bit of narrative schizophrenia, as Koontz switched perspectives so often that readers sometimes felt unintentionally dizzy. Yet it, too, has paved the way for The Silent Corner in its fantastical presentation of some of Koontz’s most enduring themes: if you mess with nature, nature will push back; human beings, while good, suffer an inclination to evil; and God has some pretty mysterious tricks up his sleeve for helping us heal our self-inflicted wounds, one of which is redemptive suffering.

Not that God is mentioned all that explicitly in many Koontz novels; after all, his target audience is massive. Koontz is adept, however, at slipping in Catholic truth exactly when it makes the most sense for a reader to realize its veracity. Call it literary evangelization.

I can give one example without spoiling things. After a particularly menacing scene in which we have come to value Jane Hawk even more as a mother than as an elite soldier, she offers this line: “They said that if someone harmed a child, it would be better for him if instead he were hanged about his neck with a millstone and drowned in the depths of the sea.” That’s Matthew 18:6, and if you’ve followed the novel to this line, it will be nearly impossible to disagree with her on this point. If Koontz’s skill doesn’t make his readers all the more pro-life, it’s hard to say what will.

Moments like this throughout the book—most of them more implicit, all of them worthy material for meditation—prove Koontz to be something more than a bestselling author who happens to be Catholic. Through the skill of his art, Koontz is realizing the valuable role of a popular literary evangelist, one whose stories attract readers from east to west in the hopes of guiding them to the fulfillment of transcendent beauty.