Apart from bills, a stubborn spouse or hungry kids, what gets you out of bed in the morning? (For clergy and religious: Apart from bells, a congregation or a superior, what gets you out of bed in the morning?) More of a night owl and a melancholic myself, rather than an early riser with a sunny disposition, I recall Fulton Sheen’s saying there are two ways to start the day. “Good morning, Lord!” or “Good Lord—morning!” Over time, starting the day in the second way will become unbearable.

We need some bright light in our lives, some hint that there is at least a possibility for momentum in the right direction, a hope that at least some part of the future could be better than the present—something that can get us out of bed in the morning. Recently, I found more than 20 bright lights.

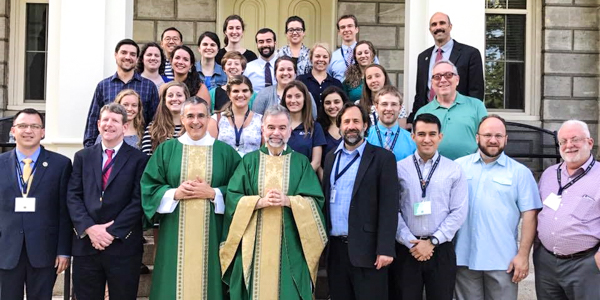

Last week, Saint Charles Borromeo Seminary in Philadelphia hosted the Fifth Annual “Boot Camp” for Medical Students, sponsored by the Catholic Medical Association. About two dozen medical students from across the country attended the camp. There were technical presentations, of course, on fertility, euthanasia, and law. There were also presentations on topics that these capable young people need and almost certainly didn’t get in their undergraduate studies: Christian anthropology as a foundation for moral law and good medicine; formation and examination of conscience for doctors; habits of prayer and sacraments for doctors; and elements of spiritual combat for Catholic doctors.

While the students were vocally grateful for all of that, they were most visibly grateful for the opportunities for fellowship with like-minded peers and mentors, faithful Catholics who could someday become colleagues and friends. They were glad to be reminded that they were not unique and not alone.

Knowing that such talented, generous and faithful Catholic young people are on the path to becoming doctors was uplifting. They are welcome bright lights in a time of storm clouds and encroaching gloom.

As I observed the proceedings throughout the week, what I saw was heartening—and sobering. The students there will be getting their degrees and licenses, residencies and fellowships in the coming years, and will do so in a context—legal, economic, scientific, social, moral, spiritual—that will almost certainly be even more hostile to them than what faithful Catholic doctors face today. New technologies will be available that will stretch to the breaking point our understanding of conception, birth, gender, sex, death, and even human identity itself. In the United States, where I write, the way is being paved to make acceptable “palliative care” and “death-with-dignity” where these are but euphemisms for euthanasia—ultimately, leading to a purge of the elderly, the handicapped, and the unwanted. At the same time, economic exigencies and legal pressure will be applied to tomorrow’s doctors to endorse, facilitate, and ultimately perform, under the guise of “care,” those acts which Catholic teaching has always judged to be morally wrong. It’s not hard to discern already a future wherein bad medicine and worse morality are deemed good policy and binding law.

What to do? Of course, we all have to pray, strive to form our conscience according to the mind of the authentic teaching of the Church, and learn about impending challenges and threats. We can become better informed, looking for information and guidance from the Catholic Medical Association, the National Catholic Bioethics Center, and the Linacre Quarterly. We can encourage faithful Catholic doctors and priests to meet and support each other through the Holy Alliance.

We also need to remind ourselves about what is at stake as we look at Catholics in the medical field. Yes, an intelligent and diligent Catholic can become as skilled and accomplished in medicine as anyone else. The difference is that well-formed Catholics in medicine will see their work as an extension of Christ the Healer. They can care for bodies and souls in a way that no government program or federal regulator can. Frequently, well-formed Catholic healthcare providers will be the last line of defense for those who can be crushed by bad medicine and bad law. If faithful Catholics do not form and support young Catholics to be faithful Catholic doctors, then human dignity and life will be put at risk, and God’s sovereignty over life and death will be mocked and scorned.

We need to work together to ensure that faithful Catholic doctors will not become, in that unfortunate phrase, “safe, legal and rare.” We need to provide them the education that they need now, and the legal, moral and spiritual protection that they will need throughout their careers, or we will have allowed bright lights of hope to be extinguished.

When I write next, I will speak of humility and humiliation. Until then, let’s keep each other in prayer.