Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

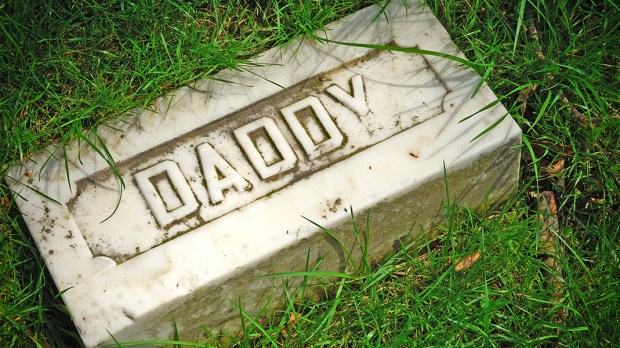

I still miss my dad, though thank God not as intensely as I did the first few years. He died eleven years ago this coming July 5th.

He’d survived the lung cancer’s first attack. Almost to the day, when he should have gotten the news that after five years he was considered cured, the doctors found the cancer had returned. He didn’t have enough of his lungs left, or a strong enough heart, to survive. They gave him nine months, but I knew him. He was a stoic. He did not fight battles he knew he could not win. He had a month or two, but not three and certainly not nine.

Three weeks later we drove up. Four days after that, I was sitting in his room at the hospice working on my laptop. My wife and our four children had run round the corner to get lunch, my mother was having lunch with an old friend round another corner, my sister was at her job running a thrift store up the road.

My dad had, I thought, weeks to live. We planned to stay another few days and go home. I’d come back. We’d made this trip mainly so our children could say goodbye to their granddad.

I had been there for a couple of hours, editing something, focused on the work, when suddenly I knew, I don’t know how, that he was breathing his last. He drew in a short, hard breath. I knelt by his head and said, “Goodbye, Dad.” He drew in a shorter, shallower breath, almost a half-breath, and then stopped.

Waving my hand toward the room because I could not speak, I got the nurse. She came in, listened for a heartbeat, and I stood hoping I was wrong, that I’d missed something, that I was going to be embarrassed, till she shook her head at another nurse who had come into the room behind me. She put her hand on my shoulder as she walked out.

The world sets traps for you. For the first few years, I would see a book he might like and start to reach for it, thinking I’d buy it for him. This happened many times and I never touched the book before my stomach exploded with adrenalin as I remembered that he was dead.

That doesn’t happen anymore. The traps now are set by sympathy.

An hour ago as I write, I was reading my Facebook page and found the writer Ben Boychuk’s article about his father, who died a few days ago. By changing just a few words — our dads were different kinds of engineers, for example, and only two years apart — I could make his article my own. Lines like “He was most at ease with numbers. … I’ve always been more comfortable with language” had me nodding my head.

Boychuk began, “I don’t know exactly what to do this Father’s Day.” He ended wishing he’d spent more time with his dad. I felt for him. I’d been there. Then I thought back to that horrible day in the hospice, and started crying.

Not many weeks after we returned home from the house that was no longer “my parents’,” but just “my mother’s,” I began to feel how much my life had changed. With my dad alive, I felt like he was standing on the windy, bitter-cold ridge above us keeping watch. Uncomplainingly, stoically, doing his duty. My family and I were safely huddled in the warm cabin down below. He was five-hundred miles away, and sick, but I felt protected. Whatever happened, my dad was there.

I suddenly realized it was my turn on the ridge. He wasn’t there. I had to keep watch, so my family could be safe and warm. I thought about him a lot five years later as my mother declined and died, and then last spring when my sister found she had late stage four metatastic cancer and when she died six months later. I wanted him to be in charge, not me. But he’d served his term.

The editors titled Boychuk’s article “What do you do on your first Father’s Day without your dad?” I’ve had twelve of them now. I’d tell him: Remember your dad. Don’t pretend the hole he left will ever be completely healed. Remember his death as well as his life, because that’s the memory that will make him most present, at least it does for me. Take your turn on the ridge, and do for your family and others what your dad did for you.

Part of the description of David Mills’ father’s death appeared in First Things, “Real Death, Real Dignity”. Boychuk’s article is “What do you do on the first Father’s Day without your dad?”