While J.R.R. Tolkien is most well known for his epic Lord of the Rings trilogy and whimsical fantasy tale The Hobbit, the author did not think either of these stories compared to a fictional tale that became the basis for everything he wrote. First called the Tale of Tinúviel, the story was born out of his own deep love for his wife, Edith.

In a letter to his son Christopher a year after his wife’s death, Tolkien wrote about the origins of this tale.

I never called Edith Lúthien – but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks at Roo in Yorkshire (where I was for a brief time in command of an outpost of the Humber Garrison in 1917, and she was able to live with me for a while). In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing – and dance… I will say no more now.

In the romantic fairy story, the main protagonist of the tale, Beren, sees Lúthien dancing in the forest and is enraptured by her beauty. The character Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings recounts the scene when talking with Frodo, reciting a portion of the story,

The leaves were long, the grass was green,The hemlock-umbels tall and fair,And in the glade a light was seenOf stars in shadow shimmering.Tinúviel [aka Lúthien] was dancing thereTo music of a pipe unseen,And light of stars was in her hair,And in her raiment glimmering.

It is a beautiful (and tragic) story of love between an immortal elf and a mortal man, one that is echoed in the love story of Aragorn and Arwen in TheLord of the Rings trilogy.

Tolkien noted in a letter how “The chief of the stories of the Silmarillion, and the one most fully treated is the Story of Beren and Lúthien the Elfmaiden … As such the story is (I think a beautiful and powerful) heroic-fairy-romance, receivable in itself with only a very general vague knowledge of the background.” He added in another letter that his entire mythological realm of Middle Earth is rooted in the story of Beren and Lúthien.

The so-called “children’s story” [The Hobbit] was a fragment, torn out of an already existing mythology … But the mythology (and associated languages) first began to take shape during the 1914-18 war … The kernel of the mythology, the matter of Lúthien Tinúviel and Beren, arose from a small woodland glade filled with ‘hemlocks’ … to which I occasionally went when free from regimental duties while in the Humber Garrison.

As Tolkien explained in his letter, Beren and Lúthien provided the “kernel” or as it is typically defined, “the central or most important part” of his mythology. After reading it, the story becomes for the reader a lens to view Tolkien’s fantasy realm, and echoes of the tale can be seen throughout The Lord of the Rings.

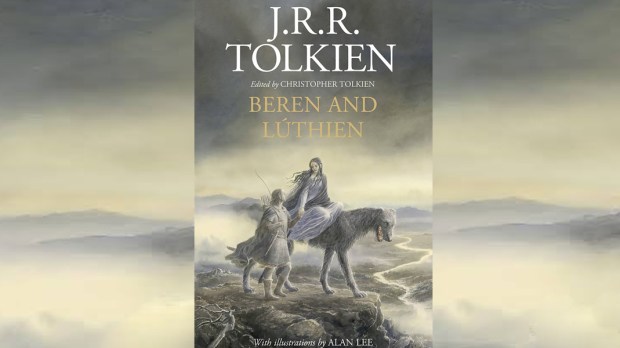

In honor of that fateful day 100 years ago when Tolkien saw his wife in the forest, Beren and Lúthienis being published for the first time in a single volume. The book being published was edited by his son Christopher who “has attempted to extract the story of Beren and Lúthien from the comprehensive work in which it was embedded; but that story was itself changing as it developed new associations within the larger history. To show something of the process whereby this legend of Middle-earth evolved over the years, he has told the story in his father’s own words by giving, first, its original form, and then passages in prose and verse from later texts that illustrate the narrative as it changed. Presented together for the first time, they reveal aspects of the story, both in event and in narrative immediacy, that were afterwards lost.”

The book is accompanied by beautiful illustrations from Alan Lee, who was a lead concept artist of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films.

To conclude, here is Tolkien reading a passage from the tale of Beren and Lúthien — and keep in mind that when he reads passages about Lúthien, he is in a certain way speaking about his wife.