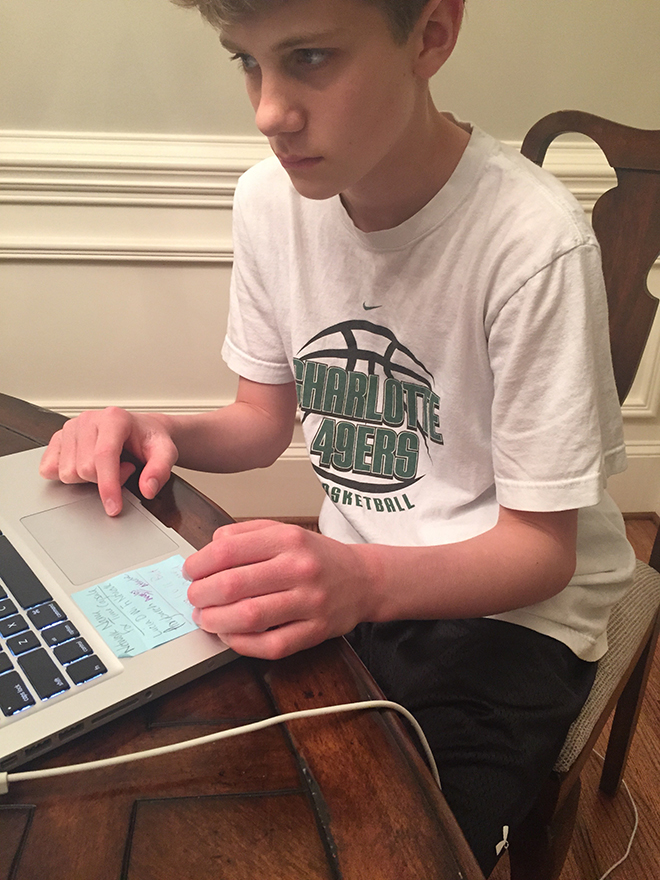

When middle school student Connor Odom road-tripped with his family from their home in Charlotte, North Carolina to Atlanta to play in the U.S. Basketball Association National, he missed the first game. As the start time for the big game approached, the 13-year-old athlete was in the hotel room shower—where he’d been for four hours—alternating between weeping and calling out for help from his parents, who stood just outside the curtain. His mother and father felt helpless, begging him to come out. “You’re all clean, Connor,” his mother said over the sounds of rushing water and her son’s furious scrubbing. “You’re going to miss your basketball game. Please come out. We love you and want to see you.”

Finally, when Connor’s episode ended and he was able to step out of the shower, it was all his mother, Lucia, could do to not rush up to hold him and comfort him, but she knew she couldn’t. For months before the shower incident, Connor had not allowed her to touch him at all: no motherly hugs, no kisses good night. It wasn’t just the onset of adolescence, Connor was in the midst of full-blown obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Bewildered by the dramatic change, his parents were trying desperately to help him, and to figure out what had happened to their son.

Overwhelming fears

OCD is a common, chronic, and long-lasting disorder in which a person has uncontrollable, reoccurring thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions) that he or she feels the urge to complete over and over. Despite the clinical terms, those who live with OCD know there is nothing “common” about it. For well over a year before the basketball game, Connor had been exhibiting increasing and multiplying signs of the disorder, launched by an overwhelming fear of germs. He developed rituals to rid himself of perceived contaminants by taking multiple, lengthy showers a day, and washing his hands until “they looked like he was wearing red gloves,” Lucia recalls. He began avoiding conversations, fearful that traces of spittle might fall on him from the other person. At times, he would only touch light switches and other objects around the house with his shirtsleeves wrapped over his hands, so some family members wore rubber gloves to help buffer Connor’s fears. Midnight runs to the grocery store for special soaps and scrubbing utensils that Connor needed became frequent.

All of this was completely unchartered territory for Connor’s family, which also included Connor’s father, Ryan, a men’s college basketball coach and his then 8-year-old brother, Owen. While Connor’s OCD symptoms ballooned, Lucia, a clothing boutique owner, spent most of her time finding and taking him to a series of doctors, psychologists, and psychiatrists. With each new expert, she hoped to find relief for her son. Though everyone Connor saw had ideas on how to battle the symptoms—SSRIs and other psychotropic drugs—no one could tell the family why Connor had developed OCD. With each new expert and treatment idea, Lucia and Ryan felt increasingly pressured to just accept the diagnosis without a cause, and focus on trying to minimize the symptoms. But the various therapies and drugs doctors recommended didn’t provide any lasting relief from Connor’s OCD. Lucia was convinced something else was wrong but she had no idea what it could be.

Life unraveling

All the while, Connor’s symptoms continued to pile up, including patterns of humming, tapping and counting. It seemed that the minute Lucia and Ryan got a grasp on one of their son’s new rituals, another would pop up. His newly formed habits could not be shortened or interrupted even if it was time for school, dinner, or a big game. Connor told his parents that he felt compelled to perform these actions uninterrupted until completion, likening each task (washing his hands, for example) to building a tower of blocks. To disturb him in the act would be akin to “someone trying to knock the tower down.” So, once the tower fell apart, he had to re-start the process and see it through. Unfortunately, too many times, the finish line would evaporate and Connor would become incapable of completing the tasks that were demanded of him, leaving him stranded and upset, like in the hotel shower.

During particularly bad weeks, Connor says, “I’d pray to God about it and for a time that helped. But some mornings I would wake up feeling I had to clean the entire house—mopping floors, laundry, everything. The first time I did this I’d never seen my mom so happy,” he says with a laugh. But, like other things, cleaning the house became a ritual for Connor, another red flag. Unsurprisingly, Connor’s world, as well as the family’s, was unraveling under the strain of an ever-growing OCD. Around the same time, Ryan lost his job at the university, along with many of his coworkers, when the entire coaching staff of the men’s basketball team was changed to bring in a new head coach. “We were sinking,” Lucia sums it up.

To cope, Lucia threw herself into research for her son: she read reams of materials and countless blogs about childhood OCD. One day, she decided to swing by the tiny neighborhood library to see if they had a specific book she’d heard of. The library didn’t have the book she was looking for, but, in a fortunate twist, the librarian led Lucia to the small collection of titles they had on the topic. “There were only six to eight books and, I don’t know why, but the only one I pulled out was Saving Sammy.”

Saving Sammy: A Mother’s Fight to Cure Her Son’s OCD by Beth Alison Maloney is the story of a mother who fought to find a cure for her son, who had inexplicably been afflicted with OCD and Tourette’s syndrome. In her mission to heal her child, Maloney uncovered research that linked his mental illnesses to a previously unknown strep infection. Despite ignorance and some opposition from parts of the medical community, Maloney found doctors who were willing to help treat Sammy with the crucial assistance of prolonged antibiotics to rid his system of the strep virus.

As soon as Lucia cracked open the pages of Saving Sammy, she felt like she’d found the missing puzzle piece that had been eluding her for so long: Connor’s OCD might be rooted in a simple strep infection.

Knowing now that the concept of an infectious disease such as Group A strep could be causing Connor’s OCD blew the doors open for Lucia. She thought back to when Connor was 11 and told her it felt like the muscles in the back of his neck were spasming and vibrating. She had taken him for a CT scan at a doctor’s recommendation, but the results were normal. The months rolled on, and Connor often had swollen glands around his throat. The ear, nose, and throat doctor noted Connor’s tonsils were swollen but had told her they didn’t see the urgency to have them removed. Thinking further, Lucia recalled Connor’s chronic stomach aches and pin-pointed other possible strep symptoms that stretched back a long period of time; only now it all made sense. And yet, Connor had never even been swabbed for strep, let alone diagnosed with it.

Saving Connor

Based on her experience with her own son, Sammy author Beth Maloney literally wrote the definitive book on what it’s like to live with PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections) in the days when it was even less recognized. “I have yet to meet a parent who comes across a doctor who knows what PANDAS is,” she said.

An entertainment attorney by trade, Maloney has become a major force in advocacy for children and parents affected by the condition. According to the PANDAS network, comprised of a group of doctors, researchers, and scientists dedicated toward awareness, “PANDAS kids may be as much as 25 percent of the children diagnosed with OCD and tic disorders, such as Tourette syndrome.” Conservatively, that means that 1 in 200 children in the U.S. alone could be suffering from PANDAS, even though the true lifetime prevalence of PANDAS (and it’s related disorder PANS) is unknown.”

Despite affirmation from lofty medical heights such as the NIMH, Columbia University Medical Center and others, PANDAS is still not recognized by what many deem the most important organization of all, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Pediatricians from across the country look toward this body for the latest in research and guidance on all disease and its effects on children. In 2014, Beth Maloney sent a letter to the AAP laying out the case for including PANDAS as a possible cause of mental illness in children. She received a polite reply asking for evidence-based research, to which Maloney provided direction to “hundreds of studies.” But the AAP has yet to publicly change their stance. Such apparent resistance baffles Maloney. Over 100 years ago, the connection was made that syphilis causes mental disorders. And now, Maloney states, “we seem expected to believe that syphilis is the only infection capable of causing mental illness.”

Controversy or not, when Lucia Odom stumbled upon Beth Maloney and her book, it unlocked a once impenetrable door. With antibiotic treatment and behavioral therapies, Connor has emerged, saying he feels like a new person. “I am a Connor I never knew because I used to be anxious a lot. It got to the point that I washed my hands 50 times a day and weird things like seeing people’s bare feet would disgust me and set me off,” he says. When countered with the thought that even people who don’t have this disorder might find bare feet distasteful at times, Connor laughs. “Yes, but that doesn’t cause them to go clean their entire house once they see them.” Point taken.

In addition to the new medication, last fall, Connor and his mother took 12 weeks off to stay near an outpatient facility in Nashville. The program there would try to help Connor overcome his OCD and anxiety that had been developing for so many years. Initially, Connor thought that going to the facility meant a loss of hope, but “they helped me so much,” he said. These days 14-year-old Connor is back in school and Lucia is back to work at her boutique and flying the country for trade shows. While the OCD behaviors have disappeared, Connor is expected to continue to use the antibiotics for at least a couple more years. (When he tried to wean off them earlier, the OCD symptoms flared up.) For now, Connor is feeling great. And, that’s not the last piece of good news: Connor’s father Ryan signed on with another university and just lead his team the furthest they have ever gone in NCAA tournament history.

Grabbing a rare moment of stillness on her back patio recently, Lucia noticed a flicker of movement on a camellia bush. “It’s Savior,” she said out loud of the bright red cardinal perched there. When Ryan Odom was a boy, whenever he saw a resting cardinal he would call out “red bird” and blow it a kiss. The game was to always make a wish before the cardinal took flight again. Last March, when Connor’s situation was bottoming out and Ryan lost his job, the family’s backyard suddenly became flooded with cardinals. Instead of making wishes on the cardinals, Lucia and Owen dedicated prayers toward Connor. One cardinal in particular seemed to always be there, and Owen decided to name him “Savior.”

For Lucia, thinking back to that time, all the lost and fearful moments Connor spent cooped up inside scrubbing and washing while his friends were playing outside, is painful. “So many things have changed, yet so many things are still the same,” Lucia says. “Savior’s still here, but instead of feeling heartbroken when I see him, Connor’s outside playing with friends and life is back where it should be.”

Common Symptoms of Strep Throat

1. Fever (101 F or above)

2. Sore throat with severe pain when swallowing

3. Red and swollen tonsils sometimes with white patches or streaks of pus

4. Tiny red spots on the roof of the mouth

5. Headache, nausea, vomiting

6. Swollen lymph nodes on the front of the neck

7. Sandpaper-like rash

Source: Centers for Disease Control