Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

When Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire team asked me to write the companion prayer book for the Pivotal Players series, I welcomed the opportunity to get to write about some figures I knew well — like Francis of Assisi — and get to know others with whom I was less familiar – like Michelangelo, who was actually quite a letter-writer and an intriguing poet.

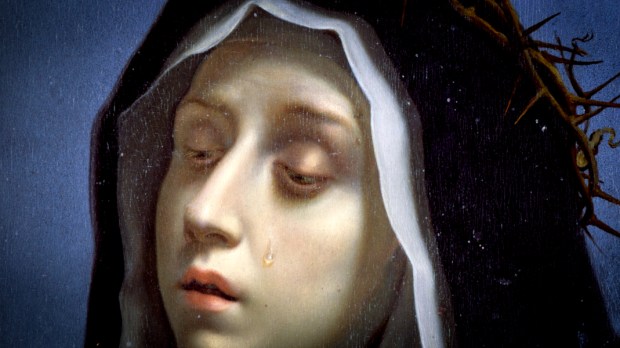

And then there was Catherine. Catherine of Siena, whom I thought I knew well enough. I had named my now 25-year-old-daughter for her, after all. But this Catherine, I discovered, was a woman whom I really barely understood at all. And who, at every turn, surprised and challenged me. I am not one who expects saints to be bland, whitewashed and predictable, but even so, as I encountered Catherine through her writings – dictated, since she could not write herself – I was continually astonished by the depth of thought, the layers of symbolism and a wild, passionate spirit that coursed strongly, even from a printed page, even eight centuries after she walked the narrow, cobbled streets of Siena.

Take blood.

At the end of his life, stripped naked, scourged at the pillar, parched with thirst, he was so poor on the wood of the cross that neither the earth nor the wood could give him a place to lay his head. He had nowhere to rest it except on his own shoulder. And drunk as he was with love, he made a bath for you of his blood when this Lamb’s body was broke open and bled from every part … He was sold to ransom you with his blood. By choosing death for himself he gave you life. (Dialogue)

Blood. Some of us are wary of the sight of it or even repulsed, but in Catherine’s landscape, there is no turning away. The biological truth that blood is life and the transcendent truth that the blood of Christ is eternal life are deeply embedded in her spirituality. We see these truths in the Dialogue, in passages like the one above, and even in her correspondence.

For in her letters, Catherine usually begins by immediately setting the context of the message that is about to come: Catherine, servant and slave of the servants of Jesus Christ, write to you in his precious blood….

The salutation is followed by a brief statement of her purpose, which, by virtue of Catherine’s initial positioning of her words in the context of the life-giving blood of Jesus, bear special weight and authority: in his precious blood…desiring to see you a true servant….desiring to see you obedient daughters…desiring to see you burning and consumed in his blazing love…desiring to see you clothed in true and perfect humility….

In both the Dialogue and her letters, Catherine takes this fundamental truth about salvation – that it comes to us through the death, that is, the blood of Christ – and works with it in vivid, startling ways. She meets the challenges of describing the agonies and ecstasies of the spiritual life with rich, even wild metaphors, and the redemptive blood of Christ plays its part here. For as she describes this life of a disciple, we meet Christ’s friends, followers, sheep, lovers as those drunk on his blood, inebriated. They are washed in the blood and they even drown in it:

This is how these beloved children and faithful servants of mine follow the teaching and example of my Truth….. Indeed, they go into battle filled and inebriated with the blood of Christ crucified. My charity sets this blood before you in the hostel of the mystic body of holy Church to give courage….(D77, p. 143) … Indeed they will pass through the narrow gate drunk, as it were, with the blood of the spotless Lamb, dressed in charity for their neighbors and bathed in the blood of Christ crucified, and they will find themselves in me, the sea of peace, lifted above imperfection and emptiness into perfection and filled with every good. (D82, p 152)

We drink the blood, served to us, as Catherine’s vision presents it, by God himself in the hostel, or inn, of the Church. We are not just strengthened by this drink: the blood of Christ renders us drunk in him, drunk with love. What does this even mean? How can drunkenness, even on what Christ gives us, be a good thing?

Perhaps it is that filled with the blood of Christ we are satiated, as the one who desires drink above all glows with contented, even joyful satisfaction when he has his fill. Although each person’s response to alcohol is different, Catherine’s usage certainly implies a picture of the happy drunk, one who has taken in what he has been desiring to the point of almost fearless, carefree joy.

But more than that, although this aspect image certainly touches on a dark edge of alcohol, if a person is inebriated, this implies a lack of control. In our earthly, physical life, this is certainly an unfortunate thing, but in Catherine’s spirituality, the imagery takes this loss of control and turns into a vision of being filled with Christ, satiated to the point that it is his power that has taken over our will, and moves us. We are in his thrall, the thrall of divine love.

In a letter to her closest spiritual advisor, Raymond of Capua, written the year of her death, Catherine alludes to the blood in a different way:

I beg you dearest Father to pray earnestly that you and I together may drown ourselves in the blood of the humble Lamb. This will make us strong and faithful. (23)

We are bathed, washed and drowned in the blood of Christ at Baptism. As time goes on, we grow in faith and love, and we understand who we are – so important to Catherine – more clearly. This act of drowning, remember, is not a negative to Catherine. Just as Paul, in Romans, describes baptism as the act of dying and rising with Christ (remember that in the early Church, adults were baptized, nude, in a tomb-shaped font in the earth, both being born again, and dying and rising at once) – Catherine understands that self-knowledge of our true selves only comes in Christ, and not simply knowing about Christ or admiring his sayings, but in the shockingly loving, bloody sacrifice on the Cross.

What do we find out? We see — in the blood – our true value, as beloved and redeemed. Eyes opened, and filled to the point of inebriation with this loving gaze of Christ, we then look at others in perhaps a different way. Christ’s blood was shed not just for me, but for everyone I see and encounter during the course of a day, every struggling, tempted, searching child of God. Catherine’s vision invites me to consider how much I really let Christ into my life, how much I give over to him, how fully I have allowed the grace of Baptism to really cleanse me, free me, and fill me, how much I am resisting, and how much I have allowed myself to consume — and be consumed.

[Excerpts adapted from Praying with the Pivotal Players used with permission – Ed]