Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

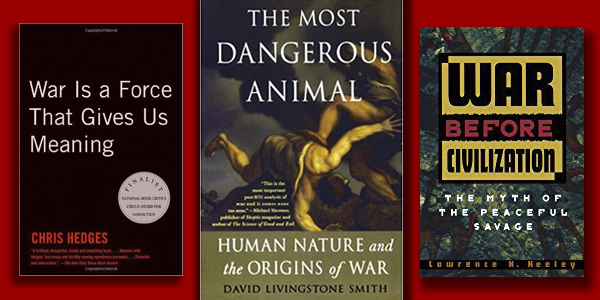

When my #3 son enlisted in the Missouri National Guard (gosh, has it been eight years ago?), I asked him as a Christmas gift to find me some books on the origins of war. He found three: War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage (1996), War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning (2003), and The Most Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War (2007).

I tried reading them immediately but it was a sluggish, on again off again effort. My #4 son, also in the Missouri Guard, was by then in Afghanistan. There was something about having a son in a war zone that prevented me from reading them. I could not quite bring myself to open them; I did not want to know about it.

I wasn’t worried for my last son’s life. He was in communications, safe on a base, though war zones aren’t called “war zones” without reason. It was more a fear he might see something, encounter something, or find something of war or of himself that would affect him adversely. The only actual combat he saw was the Great Barracks Nerf Gun Battle (I was one of the parental arms suppliers).

If only war were that, just that.

With my son home safe now two years, finishing his degree in computer science, I was finally able to pick up the books my older son sent and read them all. My discontented conclusion: war and killing and weapons seem ingrained, almost implanted within us as a Shakespearean truth, “the fault is in ourselves.”

In Lawrence H. Keeley’s War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage, the anthropologist at the University of Illinois at Chicago takes a Hobbesian depiction of human life in prehistory: “nasty, brutish, and short” is the brief summary. It is nothing like the idealization of “man in nature” pushed by Rousseau and generally adopted by Hollywood. Popular films show us noble Native Americans, tribal Africans, Brazilian rainforest people, Australian Aborigines, wise and gentle, living in harmony with the environment and at peace with one another. Not so, if Keeley’s calculations are anywhere near correct. Ancient prehistoric warfare was nearly constant and very lethal. If death and casualty rates from primitive war and inter-village raiding were transferred to the 20th century, the world would have suffered 2 billion or so deaths. Archaic societies could approach a 65 percent casualty rate, or higher. The “peaceable children of nature” Rousseau imagined were imaginary. Modern societies are no more or less violent than primitive ones but, generally speaking, they are less lethal.

With War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning, former war correspondent Chris Hedges uses irony in his title. War has no transcendent importance, even as he writes that war “gives us purpose, meaning, a reason for living.” So do addictions, when you think about it. “The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug, one I ingested for many years.” He is sketchy on the origins of war but vividly adept at showing the results once it is underway and revealing the psychological damage survivors suffer when it is over. One reviewer called it “angry and articulate,” but it leaves a pointless melancholia.

David Livingstone Smith, a philosophy professor at the University of New England and cofounder of the Institute for Cognitive Science and Evolutionary Psychology, takes an interdisciplinary tour of war with The Most Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War. He crosses paths with anthropology and Hollywood, psychology and biological evolution, prehistory and tribe-on-tribe violence, propaganda and dehumanized enemies. He lingers on the sheer brutality of battle, and killing, and the way humans have of ignoring it. He quotes General Sir John Hackett, on sanitized movie scenes: “Men blown up by high explosives in real war… are often torn apart quite hideously; in films there is a big bang and bodies, intact, fly through the air with the greatest of ease. If they are shot … they fall down like children in a game, to lie motionless. The most harrowing thing in real battle is that they usually don’t lie still; only the lucky ones are killed outright.” Battle in its horror should be viewed raw, he says. It won’t stop war; the most we may hope “is for men to detest it more than they enjoy it …”

A small step, he calls it.