Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

On the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this series of articles looks at how the Church responded to this turbulent age by finding an artistic voice to proclaim Truth through Beauty. Each column visits a Roman monument and looks at how the work of art was designed to confront a challenged raised by the Reformation with the soothing and persuasive voice of art.

“Sin and sin boldly,” Martin Luther exhorted Philip Melanchthon in 1521, when his collaborator wavered over the Reformation’s rejection of penances, as he reminded him to “let your trust in Christ be stronger.” In his blind enthusiasm, Luther promised that justification was so great that “No sin can separate us from Him, even if we were to kill or commit adultery thousands of times each day.”

These words carried a powerful echo through a world where the proud achievers of the Renaissance grew tired of the humiliating, messy and often downright ugly practice of confronting one’s sins in the confessional. The Counter-Reformation urgently needed to re-awaken the need for penance and penitential practices among the faithful, but it needed to do so by lifting up rather than beating down. Art came to the rescue by proposing models of confession and contrition that would stimulate the faithful to emulate them.

One of the very first of such models was produced by Titian in 1566, just 3 years after the close of the Council of Trent. A Venetian, Titian had come to Rome to work for Pope Paul III the year after he had opened the Council and personally went to one of the sessions in the period when the topic of Penance was discussed. As a young man, Titian had earned wealth and fame by delighting Europe with his sensual mythologies and haughty portraits. But the mature Titian had also known great loss after successive deaths of his wife, daughter and grandchild.

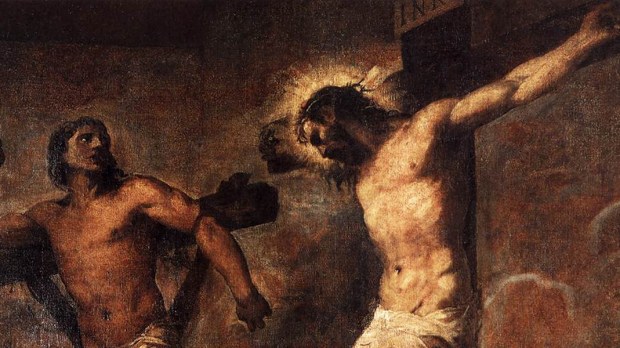

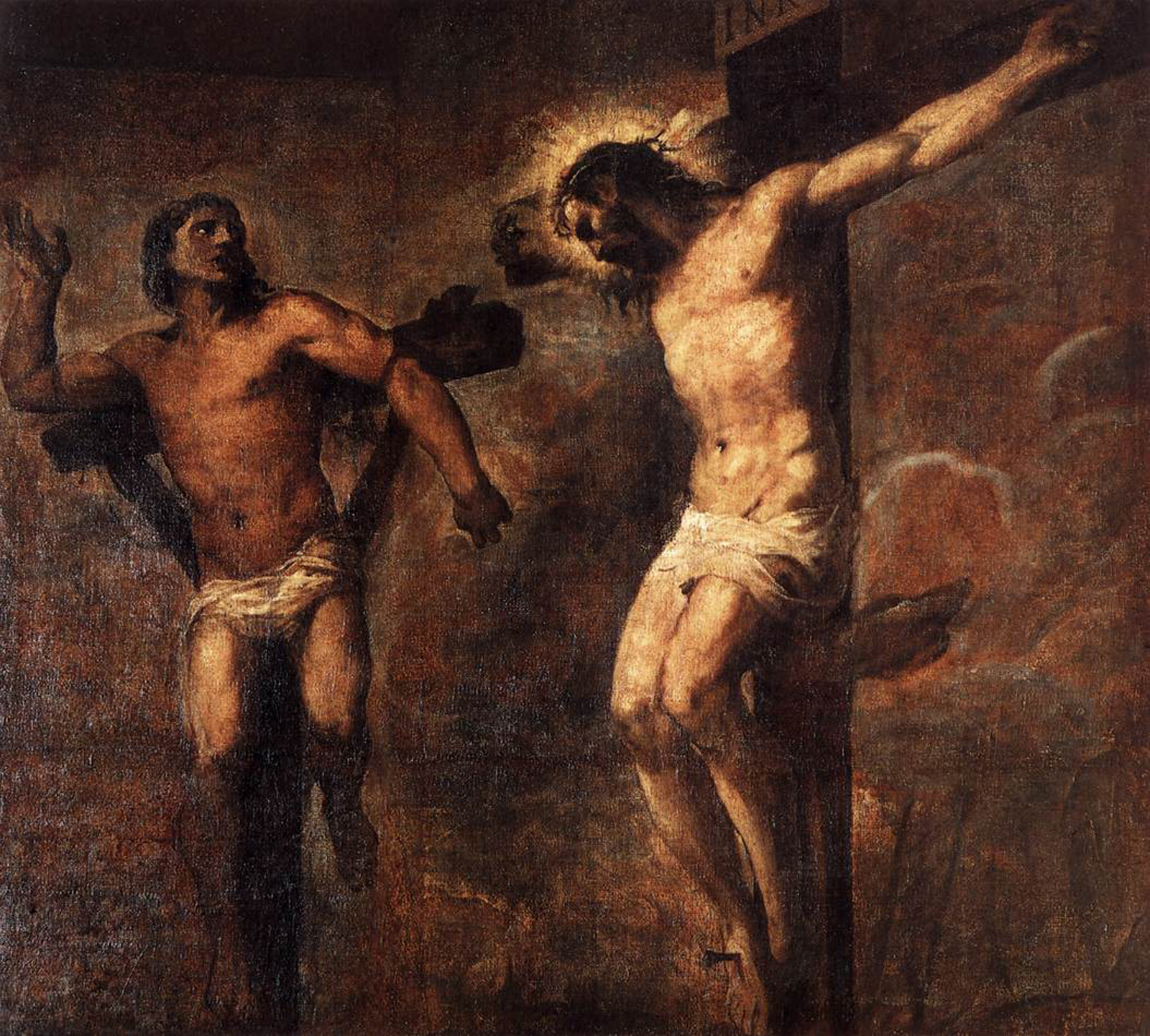

Titian produced Christ and the Good Thief as part of a 16-foot high painting of the Crucifixion, but this startling composition was the object of his focus as the very image of the sacrament of Confession.

The composition excludes the bad thief, who has chosen to reject Christ. Instead, the pair are raised high above the spears of the Roman soldiers, even as the darkness of death encroaches.

The good thief, impelled by a sudden hope, finds a last strength in his body to speak, to try to raise his hand in supplication. Confessing his guilt—“we have been condemned justly, for the sentence we received corresponds to our crimes, but this man has done nothing criminal” (Lk 23:41)—he finds mercy as Christ, almost dead himself, promises that “today you will be with me in Paradise.” His penance paid on the cross, the thief dies at peace.

Titian captures the intimacy of this moment as if in a confessional. The thief is turned towards the Lord, the light that awakens him, while Christ is turned sideways as in the confessional, without shaming the penitent. The daring perspective not only isolates the two figures in the powerful moment of redemption, but Jesus’ out-flung arm invites us, too, to share our sins with him, to shoulder our penance and bask in the warmth of His mercy. Titian’s sensuality, so often employed to portray mythological bedchambers, creates an compelling atmosphere for the intimacy of confession.

Titian’s powerful work expressed the forceful desire for conversion of a searching soul, but the Counter Reform wanted to spread a wider net. Confession and penance had been stigmatized by the Reformers with words like “impious, tyranny, pestilence, perversion, monstrosity and butchery.” With such brutal epithets, how could the Church convince the faithful of the beauty of coming clean with the Lord and being renewed by his forgiveness?

The Church turned to Mary Magdalene – apostle to the apostles and confidante of Christ—but also, thanks to a homily by Pope Gregory the Great, the ultimate model of repentance. Much like St Jerome, Mary Magdalene never went out of style; she just adapted to suit the evangelical needs of the Church. A richly robed noblewoman in the middle ages, she then became the passionate mourner under the cross in the Renaissance to return in the Counter Reform as the ultimate model for penitence.

Mary Magdalene attracted famous followers, including the Counter reformation noblewoman-turned-saint Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi and the extraordinary poetess Vittoria Colonna, so admired by Michelangelo. Colonna wrote series of sonnets to the saint and also acquired Titian’s startlingly lovely penitent Magdalene.

Mary Magdalene became one of the most popular subjects in Counter-Reformation Rome, painted by Carracci, Caravaggio and most every other major artist. No longer a well-dressed noblewomen, nor an emaciated zealot, she became a luxurious figure, whose evident beauty and attraction were no longer for things of this world but to inspire people to the wonders of heaven.

Of the many Mary Magdalenes Guido Reni painted, this version for Roman cardinal Antonio Santacroce was the most successful. The saint, swathed in heavy draperies, reflects a sensuous warmth in her soft limbs, but instead of leading the viewer to impure thoughts, she catches the gaze and redirects it to heaven. The lower half of her body is encased in stone, like a self-designated tomb. Her robe, instead of the usual fiery red, has been dulled with a cool blue, a tempering of human passions. Roots lie by her side, indicative of her penitential fasts, while the cross and skull allude to her self-mortification following the example of Christ. The upper part of her body appears warmer as her golden tresses part to reveal her luminous chest; Mary bares her heart to the Lord, and in doing so becomes a beautiful depiction of the sacrament of Confession. Angels welcome and comfort her, opening the way to heaven for this saint who makes penitence chic. Much as movie stars and models become advertisements for products of superficial beauty, Mary Magdalene became a poster child for an interior cosmetology.

The very definition of sin grew blurred in the Reformation as John Calvin denied a difference between mortal and venial sin. Listing sins, classifying sins, seemed to the Reformers a pernicious activity. After all, offending the all-pure God was an infinite offense whether in the form of adultery or an uncharitable word. Art was asked to give the faithful a new way to look at their sins and their implications for one’s relationship with Christ.

In a profoundly personal painting for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, Annibale Carracci offered a moving

testimony to the effects of sin, confession and mercy. Christ, crowned with thorns, is depicted as if through a window where the figures are the same size as the viewer. They fill the space, making it impossible for us to escape the immediacy of the scene.

The exhausted Christ, fresh from his flagellation, is given to renewed torment as the Roman soldiers dress him in a robe and crown Him with thorns. One figure in the background appears to be calling his companions to come and mock Christ, while the other in the foreground gingerly affixes the heavy crown to his head. The open space in the composition makes us uncomfortably present, a reminder that those thorns that bite into His flesh are our sins. Jesus’ reaction is mesmerizing. No anger or distance here, the gentle gaze speaks of love for sinners, and the bound hands of Christ reach out to try to gather one more soul to Him.

Is He reaching for the jailer or for us? Either way the message is clear, no one is beyond repentance and no one is beyond redemption.