Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

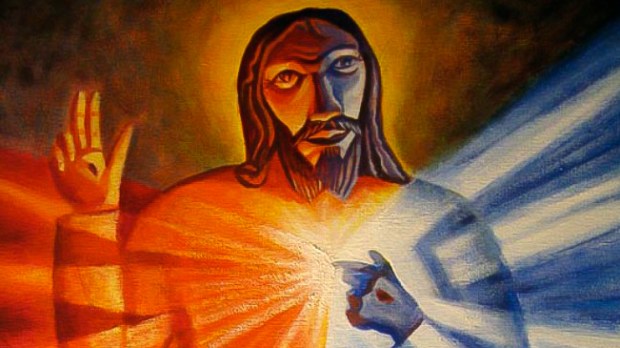

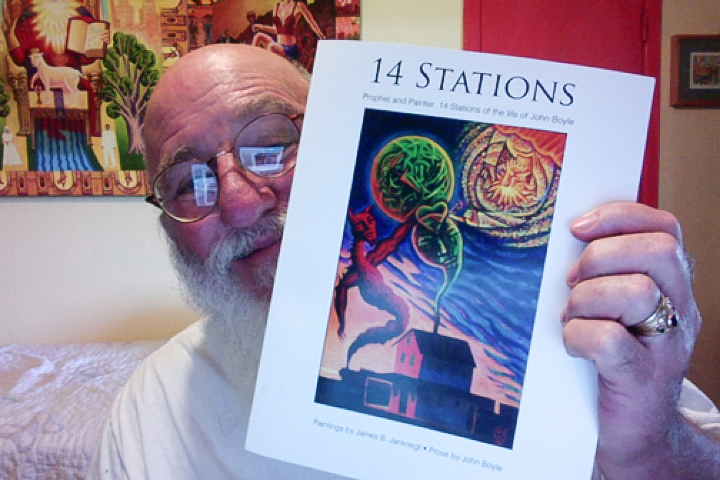

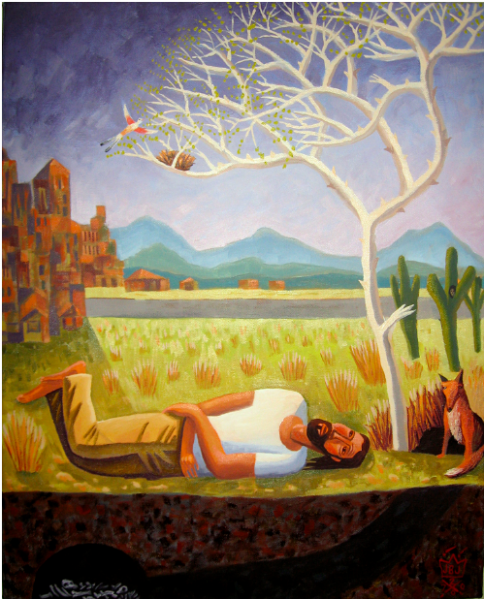

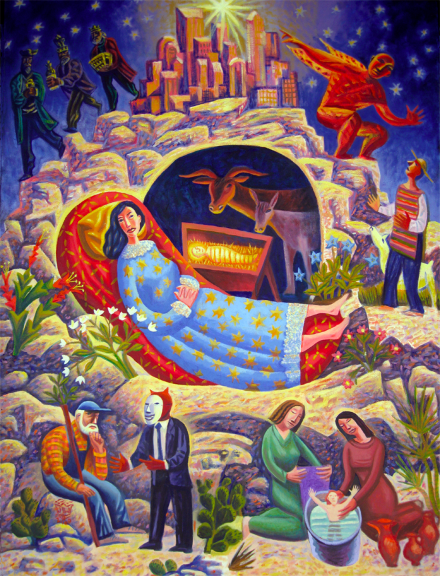

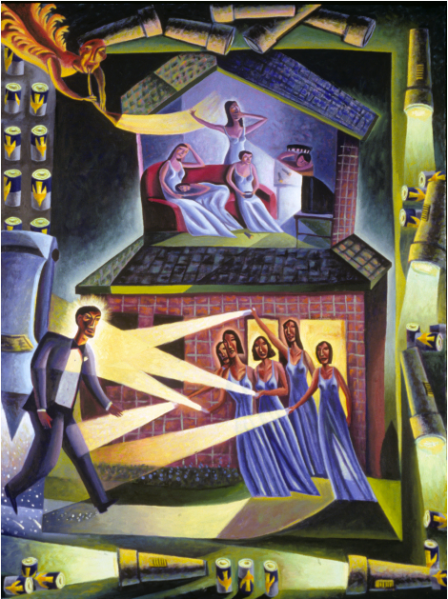

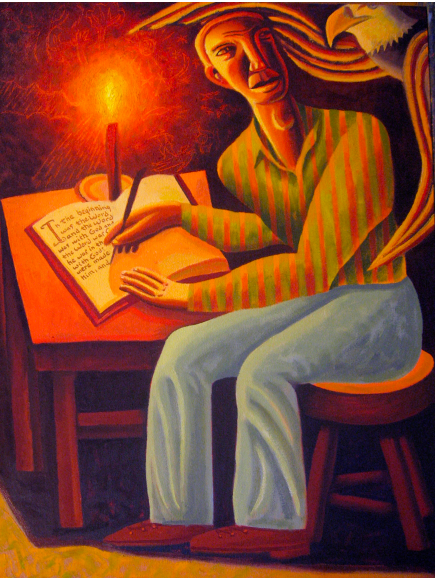

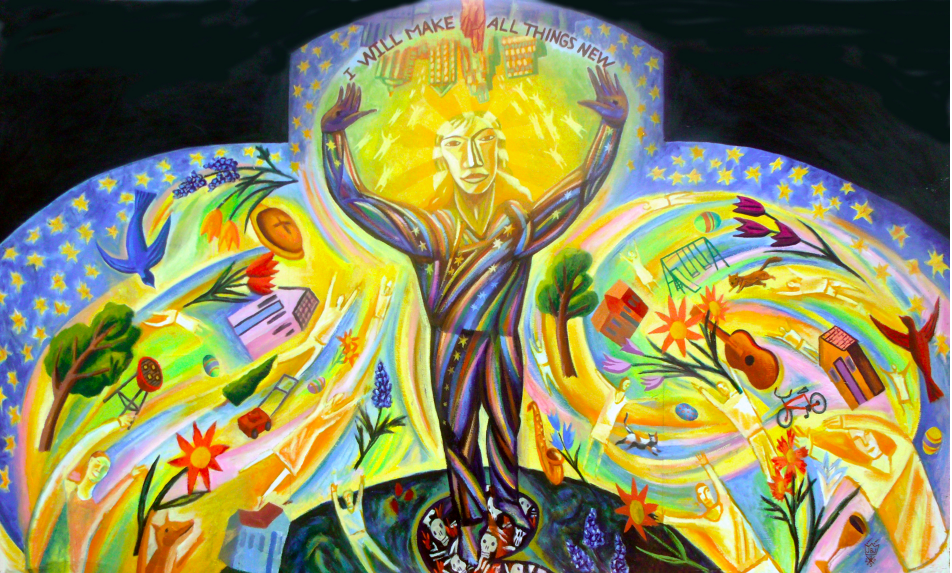

Catholic artist James Janknegt lives and works at Brilliant Corners Art Farm in Texas, where he and his wife also run a summer art camp for kids. Janknegt, 64, recently released a lavishly illustrated book of Lenten Meditations based on the parables of Jesus. He discussed his life and work with Aleteia contributor Simcha Fisher.

Simcha Fisher: You converted to Catholicism in 2005. What led up to that?

James Janknegt: When I was a teenager back in the 70s, there was a nationwide charismatic movement. I was Presbyterian at the time. There was a transdenominational coffee house at University of Texas, with the typical youth band playing Jesus songs. There was a frat house we had taken over. We had 20 people sleeping on the floor; it was crazy. A super intense time.

What kind of art education did you have?

I went to public high school, and they didn’t teach much about art history. I would look at books at book stores, and that was my exposure to art. We had a rinky-dink art museum at University of Texas, not much to speak of. After I had this deepening of my faith as a teenager, and really wanted to follow Jesus 100 percent, I was really questioning whether it was legit to become an artist. I didn’t know any artist who were Christians, or Christians who were artists.

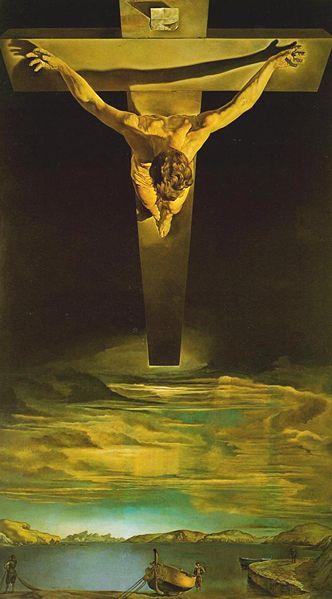

Thumbing through the bookstore, I found Salvador Dali. The book was cracked open at “Christ of St. John of the Cross.”

That still, small voice that’s not audible, but you know it’s authentically God speaking to you — it felt affirmed. Yes, go forward to be an artist and be a Christian. Those are not incompatible.

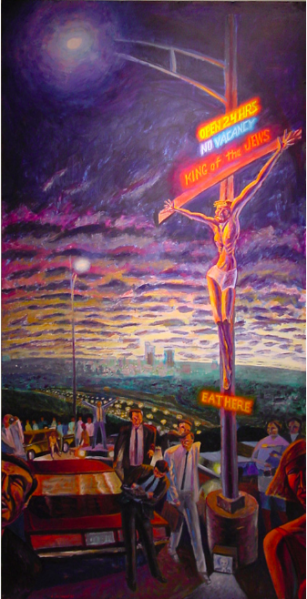

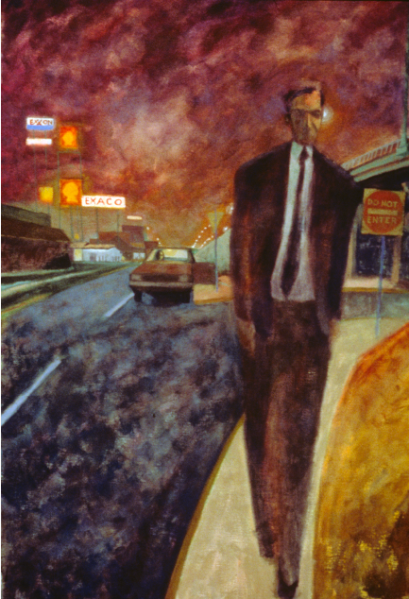

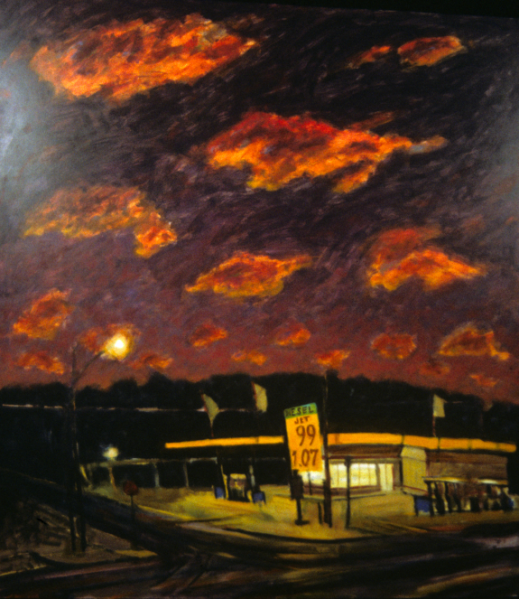

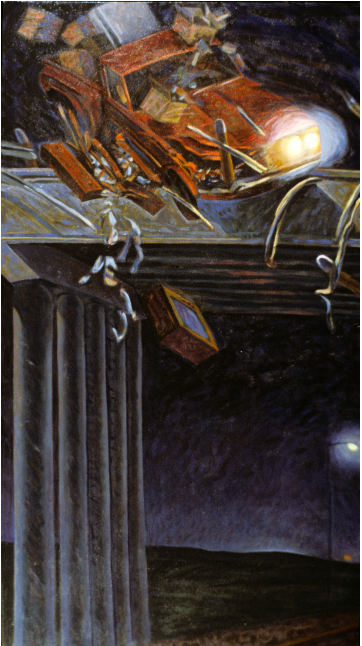

Your pieces move from dark and lonely to radiant after your remarriage and conversion to Catholicism — that shift that you define as going from “diagnostic to celebratory.” But even in the “celebratory” stage, there is drama, even agony, along with ecstasy in your pieces.

When I was involved in that youth group, they were very super-spiritual, filled with the Holy Spirit, thinking, “Now we can do everything!”

But we never looked internally to see if there are psychological problems alongside your spiritual life. My dad was bipolar and manic depressive, in and out of mental institutions and jail. I met a woman at that Jesus freak outfit, and we got married. I carried a lot of baggage into my first marriage, that I hadn’t dealt with at all. I went to grad school and my marriage fell apart.

Getting divorced ripped the lid off. All this stuff I had repressed was all bubbling up and coming to the fore. Questioning not my faith, but my ability to be faithful. Can I hear Him and be obedient to Him and do His will? It was a very dark time.

When we look at your paintings chronologically, it very obviously mirrors different stages in your life. Is it strange to have your whole life on display?

You take that on when you become an artist. It’s very self-revelatory. It’s part of the deal, if you’re gonna be an artist, to be as honest as you can. I think that’s the downfall of a lot of bad religious art: It’s not technically bad, but it’s just not honest. We live in a fallen world. Bad things happen.

That’s part of life, and that has to be in your painting. You can’t paint sanitized, Sunday school art.

But you do seem to create art that has very specific meanings in mind. Do you worry about limiting what the viewer can get out of a piece?

There’s a painting I did of Easter morning zinnias. They look like firecrackers; Jonah’s on the vase; in the corner, there’s an airplane.

I just needed something in the corner to make your eye move into that corner! People were trying to figure out what it meant, but sometimes an airplane is just an airplane.

To me, the role of art is to make something beautiful. Very simple, that’s the prime directive: Make something beautiful.

It doesn’t have to be figurative or narrative or decorative. But my feeling is: The history of our salvation, starting with Genesis to Revelation, is indeed the greatest story ever told. What’s better? As an artist, why wouldn’t I want to tell that?

How does the secular world respond to your works? They are full of parables and Bible stories, but also unfamiliar imagery.

A painting is different from a sentence or a paragraph. Paintings deal with visual symbols. I’m trying to take something that was conceptualized 2,000 years ago in a different culture, keeping the content, in a different context.

It’s almost like translating a language, but with visual symbols.

I have a definite idea of what I’m trying to get across. But you [the viewer] bring with yourself a completely different set of assumptions and experiences, and I have no control over that. I don’t want to.

When I look at a painting, it’s a conversation. I’m talking into the painting, and the painting is talking to you.

Part of the problem today is that we do not have the same visual symbolic language. In the Renaissance or the Middle Ages, the culture was homogeneous, and symbols were used for hundreds and hundreds of years. If I put a pelican pecking its breast, no one [today] knows what that means. We’ve lost the language. So it’s challenging.

Are you inventing your own modern symbolic language? I see birds, dogs . . .

You kind of have to. It’s a balancing act. In art school, they say, “Just express yourself! You’re painting for yourself; it doesn’t matter what everyone else gets out of it.” I’m not doing that. I’m trying to communicate with people.

Tell me about the state of religious art right now.

People complain about how there’s no good religious art. But there’s a lot of good art out there; you just have to search for it. I feel like I’m hidden away, in this weird place between two cultures, but they are out there.

In our time, people who collect art aren’t religious, and people who are religious don’t collect art. And for an artist, in the Venn diagram, you’re in the place where it says “no money.”

If you could just find an artist you really like and ask them if you could buy a piece for your home shrine.

If every Catholic could buy a piece of art from a living artist, think how that would impact your life, and the life of the artist. You could give them a living.

Read more:

What is the best way to support Catholic arts and letters?

Your farm is called “Brilliant Corners Art Farm.” Is that name a reference to Thelonious Monk?

It is! But it also has a hidden spiritual meaning. Honesty is the light. If you’ve got brilliant corners, then the whole room is lit up.

You can find more of James Janknegt’s art and purchase his new book on his website, bcartfarm.com.