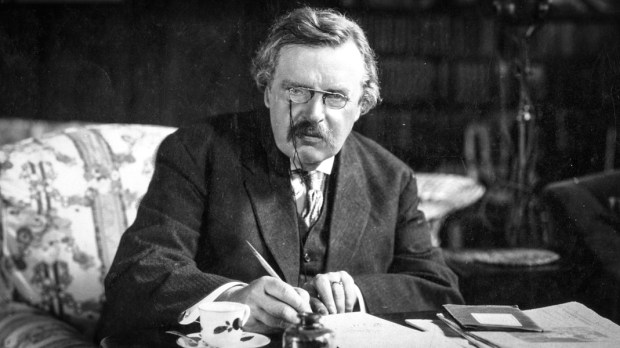

G.K. Chesterton is not yet a canonized saint. Though his cause was opened by the Diocese of Northampton in 2013, there is not much news about the progress of this beloved English writer.

Still, his fans number greatly among the faithful, as Catholics and Protestants alike quote the man and praise his eloquence, wit, liveliness, and orthodoxy.

For this reason, I, as a faithful Chestertonian, hope that the Lord’s plans involve the man behind so many great works (including a poem about the University of Notre Dame, go Irish!) to be raised to the altar.

Read more:

The woman beside the man, Frances Chesterton

Should that day come, there will come the need to assign some patronage to the English literary giant. To do so, however, would be quite difficult; Chesterton was a journalist; he wrote about every subject under the sun; he was a Catholic; he wrote about every subject above the aforementioned firmament.

With dozens of books, hundreds of poems, and thousands of essays, it seems nay impossible to boil the polymath to one subject of patronage. But impossible it is not! For all the man’s many skills, he is best known for one – he was an inveterate jokester.

Take, for example, his poem “On Professor Freud”:

“THE ignorant pronounce it Frood,

to cavil or applaud.

The well-informed pronounce it Froyd,

But I pronounce it Fraud.”

In the short course of four lines, Chesterton has managed to poke fun at not only the infamous Sigmund Freud, but also both the educated and uneducated. His wit is so precise that he can brandish it in a 20-word prank as well as he could in an entire comedy. If not sainted, we may all at least agree that he is skilled.

If that is not enough, however, consider for a moment the brilliant lunacy which Chesterton titled The Man Who Was Thursday.

The book is a page-turner, but also mind-boggling confusing at times; this should be no surprise as Chesterton dedicates this book to his friend E.C. Bentley with a poem that says, “Oh, who shall understand but you; yea, who shall understand?” raising the question of why Chesterton would publish a book indecipherable to all but one. As a result, this text, for all its literary excellence, appears so obviously a prank upon its readers that the seminarians at the Pontifical North American College in Rome chose to air their (very)off-Broadway rendition of the book on April 1. This date is well known for its connections to the jocular and boisterous, as its common name, “April Fools’ Day,” is used as a parlay-word for a myriad of pranks played between friends.

What better role could Chesterton play than the patron of such light-hearted fun as a well-meaning joke? Was it not he who said: “It is the test of a good religion whether you can joke about it”? Is the litter of humorous Christian quote memes not composed predominantly as Chesterton? No author before or since has had such a way with words as to make every text a goldmine of one-liners.

Some may say it is wrong to boil Chesterton down to a mere clown; they are very wrong. I doubt that Chesterton would ever claim to be anything more than a clown (excepting, of course, his claim to be a Christian!). He was frivolous in all things (of his own profession he stated: “Journalism largely consists of saying ‘Lord Jones Is Dead’ to people who never knew that Lord Jones was alive”), not because he thought little of them, but because he thought greatly of them, and to think greatly of them was to enjoy them. Unfortunately, to the rest of us, enjoyment can often smell slightly of insanity.

We need the intercession of Chesterton’s comedy to rid ourselves of this false sense of insanity. In his essay “A Defense of Nonsense,” in which Chesterton argues for the kind of literature offered us by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, he expresses the sentiment that “Religion has for centuries been trying to make men exult in the ‘wonders’ of creation, but it has forgotten that a thing cannot be completely wonderful so long as it remains sensible.”

Chesterton, through his noble vocation as a clown with an inkwell, enabled us to exalt in the wonders of our faith through his nonsense and frivolity. He undoubtedly would be willing to replace his pen with his prayers to the same effect now that he has joined the choir invisible.

As a closing argument, I offer what is the most virulent proof that G.K. Chesterton is an extraordinary patron of jest — what are undoubtedly his greatest words ever penned: “The poets have been mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese.”

Read more:

5 Tips on how to read G.K. Chesterton