Help Aleteia continue its mission by making a tax-deductible donation. In this way, Aleteia's future will be yours as well.

*Your donation is tax deductible!

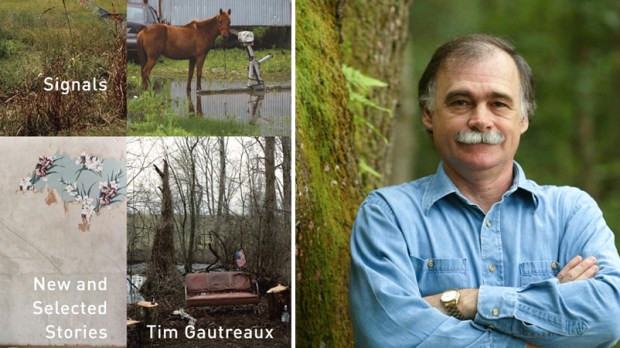

Like so many of his characters, Tim Gautreaux (The Missing, The Clearing) labors under the radar.

Still, the novelist and short story writer’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Atlantic, Harper’s, and GQ, and has earned him the John Dos Passos Prize, previously awarded to the likes of Graham Greene, Tom Wolfe, and Shelby Foote.

He also has earned the respect of his peers. Two recipients of the same prize, Annie Proulx and Jill McCorkle, praised Gautreaux for his just released collection of new and selected stories, Signals, calling it “rich,” “brilliantly crafted,” “prime reading pleasure.” If the blurbs on his new book are any indication, he is a writer’s writer.

He also happens to be Catholic.

A few years ago, Dana Gioia (“The Catholic Writer Today”) and Gregory Wolfe (“The Catholic Writer, Then and Now”) ignited a conversation about the state of Catholic fiction and poetry today. It was mostly an in-house conversation, one in which literary Catholics took a long hard look at their own past, present, and future. (The discussion rages on this month at Fordham University, which is hosting a conference on “The Future of the Catholic Literary Imagination.”)

The question was this: Where are the great Catholic writers today? Have they vanished or become anemic about their faith? Or have they simply taken a different tack and gone unnoticed?

Flannery O’Connor, whose stories were known for their larger-than-life quality, famously said: “For the hard of hearing you have to shout.” But Wolfe argues that where the grand gestures of modernism have largely faded, contemporary Catholic writers are out there; they just tend to “whisper,” writing “more intimate, domestic tales” that capture “the actual blood of everyday human experience.”

This is Gautreaux’s territory in Signals. His characters, often Cajuns, are people of American pragmatism, southern manners, and rural handiness. We meet blue-collar tradesmen, obsessive collectors, and distracted family members who navigate the (mostly) ordinary occupations, families, and towns where they work and live. In a word, it’s a world of whispers, where what’s unsaid is deafening.

That’s not to say that Gautreaux doesn’t have his influences. As with the work of any Catholic writer – especially a Southern one writing short stories – Signals does reflect the work of O’Connor. In fact, one story, “Idols,” is a kind of sequel to two O’Connor stories that sees two of her characters converging on a crumbling Mississippi mansion. Gautreaux is also from Louisiana, the home of another giant of Catholic literature, Walker Percy – and in fact, in 1977, studied with Percy at Loyola University.

But in a conversation with Image Journal, Gautreaux explains that “Idols” resulted from a request to write a tribute story to O’Connor. As for Percy, Gautreaux shares the same Louisiana settings and basic concerns – “What are the characters looking for? What would make them happy?” – but that’s about it. Gautreaux doesn’t try to recreate the magic of his predecessors. There are no embarrassing pastiches of misfits prophesying in the backwoods or searchers experiencing existential malaise in the French Quarter.

Instead, Gautreaux is a writer interested in “the importance of objects.” In “Wings,” a widowed woman goes on an unexpected adventure to a flea market with a lonely neighbor who admired her late husband, and buys a metal emblem that captures her resentment and unknowing. In “Attitude Adjustment,” a local priest, physically and mentally injured by an accident, sets out to retrieve a stolen shotgun for his gardener to save him from family shame, only to find himself doing prison time. In “The Furnace Man’s Lament,” a repairman in Minnesota gets a service call during a snowstorm from someone with a broken heater, and ends up meeting a young boy who becomes his apprentice, leading him to a powerful realization about his life’s direction.

Signals delivers plenty of raucous action and laugh out loud dialogue, sometimes in the same story. But at his best, Gautreaux is a meditative poet of the handymen, “invisible” people who tune pianos and exterminate bugs and rewire radios, who have deep knowledge of how things work yet find themselves struggling to make their own lives work. Some have wounded bodies, some wounded minds, but nearly all of them have wounded souls, trying to make a new beginning or settle an old score through the things they know and love.

The stories are filled with priests, Mass-goers, and the sacraments, especially the sacrament of Confession. But Gautreaux, a lifelong Catholic, seems perfectly at ease in his faith, and less concerned with convincing his readers of its truth than simply dwelling in it and watching how it shapes life in this world. The result is a world of mechanics that’s anything but mechanical, a sacramental vision which, as Percy wrote in “The Holiness of the Ordinary,” confers “the highest significance upon the ordinary things of the world.”

In short, it’s a world where everywhere and always there are signals. And what’s true for his characters is just as true for readers stuck on the stories of 40 or 50 years ago: maybe what we need to do is just start paying closer attention.