Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

On the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this series of articles looks at how the Church responded to that turbulent age by finding an artistic voice to proclaim Truth through Beauty. Each column visits a Roman monument and looks at how the work of art was designed to confront a challenged raised by the Reformation with the soothing and persuasive voice of art.

Martin Luther inflamed hearts and minds with his energetic refutation of the sacrament of Penance. Laying the blame on priests whose “perilous and perverse doctrine” had divided penitence “into three parts, contrition, confession, and satisfaction,” Luther claimed that they had “taken away all that was good in each of these, and have set up in each their own tyranny and caprice.”

The Church rallied to the defense of the sacrament of Penance twice during the Council of Trent: once as it denounced the Reformers’ Doctrine of Justification in 1547 and more thoroughly in the 14th session in 1551. And once again the Church looked to art to help transmit the formal decrees of the Council into the living body of the Church.

This presented a new challenge to art: how to represent the essential role of the clergy in the sacrament of Penance. A dynamic exchange between painters and ecclesiastical patrons resulted in moving works destined mostly for intimate settings. The works, intended to excite penitential devotion among the clergy, focused on the three pillars of the sacrament denigrated by the Protestants: contrition, confession and satisfaction.

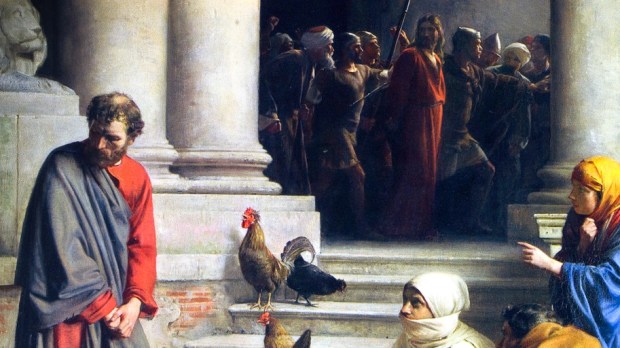

Who better to lead the iconographic charge to contrition than St Peter? He had denied Christ three times and yet it was to this apostle that Christ entrusted the keys to bind and loose sins. Peter became the model of the contrite heart in scores of portraits painted by artists such as El Greco, Ribera, Van Dyck and Guercino. Guido Reni, however, became a specialist in the image, producing over a dozen of these portraits. Never destined to hang in a church, they graced the private setting of a prelate’s home. They were to incite emulation of the Prince of the Apostles not only in his important role as leader, but also in his humble acknowledgement of his sins before the Lord.

Reni’s most famous Penitent Peter is now in a private collection in Rome. Produced around 1600, when the Jubilee year preached conversion throughout Europe, this early work by Reni with looser, more visible brushstrokes captures the immediacy of the moment. Peter is depicted as the same size as the viewer, with no background or distraction to alleviate the sorrowful scene. The work is like a mirror, inviting the prelate to emulate the example set by the first pope.

Reni brightly illuminated Peter’s bared chest, causing the eye to linger of the exposed flesh, as Peter opens his heart. His hand splayed across his skin evokes the dramatic gestures favored in this period, but also recalls the physical rebuke during the Confiteor of “mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.”

The wiry strands of his beard and the chiaroscuro crevasses of his wrinkles add a kinetic force to Peter’s contrition; even as he submits himself humbly to divine justice, his recognition of sin is active. His face turns upwards towards the source of light, hopeful in forgiveness as tears well up in his eyes and fall down his cheek. This intimate portrait of repentance put forward a model of contrition that could speak persuasively to the proud world of Roman clerics.

One of the giants of clerical reform was St Charles Borromeo, the archbishop of Milan. He encouraged each priest of his diocese, especially those with the mandate to preach, to “first purge his conscience of all impurity of sin by the sacrament of Penance.” To that end, in 1564 he designed spaces within the church intended for the hearing of confessions, which today are known as confessionals.

This confessional from the Jesuit church of San Fedele in Milan by Giovanni Taurini is a particularly beautiful execution of Borromeo’s plan. Carved from walnut wood, the box featured open sides for the penitent and a center section for the confessor, with little grills separating the priest from the penitent for both privacy and propriety.

The style was so successful that Pope Paul V adopted the form in his Roman Ritual, so one can find these confessionals everywhere in Rome, from St Peter’s Basilica to San Carlino alle Quattro fontane.

Therefore, together with the Eucharist (the altar) and Baptism (the font), the sacrament of Penance was given its own special architectural space within the church, underscoring its importance as a sacrament.

The final element of reconciliation was that of satisfaction, consisting in the penances offered by those whose sins had been forgiven. The Protestants held this practice in particular contempt, so the Church recruited artists to illustrate the ancient tradition of penitential activity with a particular focus on St Jerome.

Luther repudiated St Jerome’s claim that penance was “the second plank after shipwreck.” Therefore this 4th-century saint, who practiced what he preached, offered a powerful response to the Protestants. Jerome gave hard penances but also took up the penitential life himself by moving to the desert and translating Sacred Scripture into Latin, long before Luther’s translations. During the Renaissance, Jerome was often depicted as an elegant figure in an ornate study, but the Counter-Reformation transformed him into a penitential hero immortalized by Caravaggio, the Carracci, and Veronese, to name a few.

Of the many versions to choose from, Barocci’s St Jerome in the Galleria Borghese bears closer examination. Far from the city, the saint kneels in his cave. The sun is setting in the distance, but Jerome has his lantern to continue his work into the night. The ground is hard, the wicker basket scratchy and the sparse vegetation offers little signs of life.

Jerome holds a crucifix before his eyes and grasps a stone in his other hand with which he will inflict blows to his body in self-mortification. While off-putting to the modern viewer, “these penitential practices,” writes Msgr. John Cihak, “which seem rather severe today, can also be interpreted as a positive response to the dissolute times.” Symbols of the passage of time, from the hourglass to the skull, remind the viewer that all will be called to give an accounting of themselves.

It is Barocci’s brushwork that renders the image so captivating. The rose-colored mantle billows and falls, catching the light. Like the body about to bruise and bleed, the cloth evokes energy. The swells of cloth are rendered in broad, quick strokes, while Jerome’s face seems to be the result of high definition photography. The tiny bristles crisply delineate the aged features of the saint—fine wrinkles, swollen eyelids, parted lips—yet the hoary features of the elderly man belie his fervent, loving expression as he gazes upon his cross, his burden lightened by his fiery love of Christ.

The array of examples of clerical penitence paved the way for new commissions directed at the faithful to draw them more closely to the sacrament of Penance. In the next installment, we’ll see how the models of Peter and Jerome give way to new figures to incite the faithful to contrition, confession and satisfaction.