As we continue to remember Black History Month, let us look at a priest who, against the popular mood at the time, did all he could to fight for racial equality.

Ordained in 1912, Father Bernard J. Quinn approached Bishop Charles Edward McDonnell of the Diocese of Brooklyn and asked about the possibility of opening an “apostolate to Blacks.” Quinn saw that while the Church was busy ministering to the needs of European immigrants, the African-American population was being neglected. Bishop McDonnell, worried more about the onset of World War I, refused his petition. The bishop needed more priests to be chaplains overseas and so a new apostolate in his diocese was not on his radar.

Read more: This hairdresser slave is on the way to canonization

Quinn responded to the bishop’s need by volunteering to be a chaplain and put his idea on hold for the moment. He was sent over with an infantry regiment and before returning home, Quinn discovered a new saintly friend while in France: Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. As part of his assignment, Quinn was stationed near Alençon, the place of Saint Thérèse’s birth, and fell in love with the saint after reading her autobiography, Story of a Soul.

According to Our Sunday Visitor, “While he still ministered to the soldiers after the war, [he received] permission from his army superior to visit the home of Thérèse, where he celebrated Mass on Jan. 2, 1919, the anniversary of her birth. He noted that the experience was ‘a very great privilege because I was the first priest to say Mass there.’”

Read more: Leonie Martin: St. Therese’s “difficult sister” continues on the road to canonization

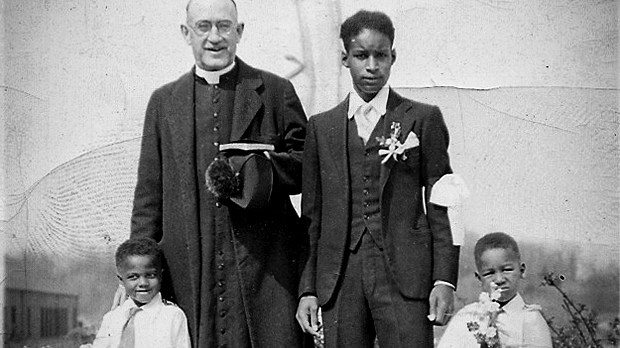

After returning to his diocese, Quinn renewed his petition and was finally granted permission to begin a new parish for African-American Catholics in Brooklyn. Quinn purchased an old Protestant church and had it “blessed and dedicated to St. Peter Claver on February 26, 1922.”

He put his congregation under the care of Saint Thérèse and would later found the Little Flower House of Providence to care for orphaned African-American children. Additionally, each week at his parish he hosted “St Thérèse novena services… Each Monday, approximately 10,000 devotees flocked to this novena where miraculous cures, both physical and spiritual, were said to have occurred.”

However, his efforts to reach out to the African-American community did not go unnoticed by the Ku Klux Klan. They burnt his orphanage down twice in the same year. This did not deter Monsignor Quinn, who rebuilt the orphanage out of concrete and brick. Even when news reached him of various death threats Quinn pledged before his parishioners, “I would willingly shed to the last drop my life’s blood for the least among you.”

Quinn was assisted in his efforts by Saint Katherine Drexel, who was also busy ministering to the African-American community in the United States. With the success of his first parish, Quinn was able to found a second mission, St. Benedict the Moor Mission, in Jamaica, Queens.

Monsignor Quinn died on April 7, 1940, after battling carcinoma. His funeral was attended by thousands of people and his legacy survives to this day. According to the New York Times, his orphanage remains “the base of operations for the diocese’s Little Flower Children and Family Services of New York program, which provides a variety of services in Queens and Brooklyn and on Long Island.”

Brooklyn Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio opened the cause for his canonization on June 24, 2010, and initiated a review of Monsignor Quinn’s life to determine if they are able to move forward in the next stage on the road to sainthood.

At a time in our country when the racial divide has stirred up many strong feelings, let us look to Monsignor Quinn and seek his intercession as we try to heal our nation.