As night shift nursing supervisor, Vera Booker had just gotten to work at Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma when the call came in: A young man had been shot in Marion, about 30 miles away, during a voting rights march.

It was nearly midnight when his friends got him to the hospital. As they lay him on a gurney, Nurse Booker pulled up his shirt and saw "his intestines sticking out of a hole in his gut about the size of a grapefruit."

Her notes told the story:

As she called the physician, she had no idea she was about to play a part in a drama that would change forever her community—and the nation.

This weekend, thousands of people from around the country—and world—are coming to Selma, Alabama, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of a movement which grew from the work of unsung heroes into the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughters; former President George W. Bush and wife Laura, and over 90 congressmen will commemorate the courage of people like Jimmie Lee Jackson who believed in the simple right of African-Americans to vote.

It is also the commemoration of a movement led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that was deeply embedded in the church, as the single evening proved: Jimmy Lee Jackson, at 26, was the youngest deacon at his Baptist church in Marion. Nurse Booker was the wife of the pastor at Morningstar Baptist in Selma, and the hospital, the primary hospital serving blacks in nine counties, was operated by the Fathers of St. Edmund and staffed by the Sisters of St. Joseph.

Nurse Booker’s heart went out to the young 26-year-old serviceman who had a four-year-old daughter, as she did. Jackson had joined a peaceful march that night that was met by brutality. When the young man stood between his mother and the state trooper’s billy club, the trooper shot him.

Jackson never recovered from his injuries. His death eight days later shocked and grieved the movement. Leaders resolved to march to Montgomery to ask the governor why this young man was killed.

The next Sunday—March 7—from the doors of Brown Chapel A.M.E church, over 600 marchers walked Selma city streets to the Edmund Pettus Bridge—named for a Confederate general—to begin their long trek to Montgomery, carrying the burden of Jackson’s death on their hearts.

But they never made it. They were stopped on the far side of the bridge by a line of mounted armed sheriff deputies and state troopers who began attacking them with billy clubs and whips, releasing 40 canisters of tear gas and 12 cans of smoke. The violence and bloodshed that injured over 100 peaceful marchers gave the day the name "Bloody Sunday."

Dianne Harris, a retired school teacher, was just 15 when she headed out with the marchers to cross the bridge that day. She remembers the pounding of horses and the thud of billy clubs hitting marchers, as tear gas burned their eyes and skin.

"We were chased all the way back to Brown Chapel, but the horse couldn’t get up the steps, so we escaped," said Harris, who with her brother Isaac had been arrested twice in marching for their mother’s right to vote.

Nurse Booker remembers the call she got that afternoon from the sisters at Good Samaritan. The Catholic hospital had become the triage center, a place of mercy and care in the midst of the shockingly violent turmoil.

"When I got there it was chaos, people everywhere, people bleeding and the smell of tear gas had permeated their clothes and skin. It’s a terrible smell and it filled the narrow hallways, she said.

The 21 pages of entries of the hospital log for that day tell the story: lacerations, fractured skulls, concussions, fractured legs, burned eyes and skin, and cuts and abrasions from billy clubs, whips and horses’ hooves.

The sight—publicized on television that night—galvanized a nation sickened by raw brutality used against innocent defenseless marchers, men women and children. King called for people of all faiths to come to Selma to join them in the march for freedom.

Sister Antona Ebo, a Franciscan Sister of Mary, was working in an infirmary in St. Louis when her superior asked her if she wanted to go to Selma. Two days later, they arrived at Brown AME Chapel with five sisters. Andrew Young, with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, looked up from the pulpit and announced: "Ladies and gentlemen, one of the great moral forces of the world has just walked in the door."

The march, known as "Turnaround Tuesday" was a statement that this was a movement gaining momentum, especially in the religious community. Sister Antona stood out with her dark skin and religious habit, and landed on the front page of The New York Times, where she was quoted, "I’m here because I’m a Negro, a nun, a Catholic, and because I want to bear witness."

This weekend, Sister Antona, along with several Sisters of St. Joseph, have returned to Selma to celebrate the Voting Rights movement, to embrace the history, and to hope and pray for an even brighter future.

"We still have much to do," said Rev. F.D. Reece, one of the original marchers who still pastors Ebenezer Baptist Church in Selma. "And we have much to be thankful for. We know the Lord has brought us through and will give us the strength and courage to keep moving forward."

The Fathers of St. Edmund continue to minister in Selma, operating a soup kitchen and senior care center. Sister Jane Kelly, a sister of St Joseph of Carondelet, and Sister Cecile Cusson, Daughter of the Holy Spirit, are two of several sisters who minister to the poor in the Black Belt region—12 counties of central Alabama that are named for the black dirt that led to cotton plantations and now are among the poorest in the state. Sister Jane and Sister Cecile drive 90 miles a day to rural Wilcox County to serve the poor at a small health clinic.

At a church-led unity march, the first of its kind, over 2000 Selma residents of all races and denominations came together March 1 to kick off the commemorative week by showing that the city has progressed since 1965 and is working together and walking together to make a better future for the city.

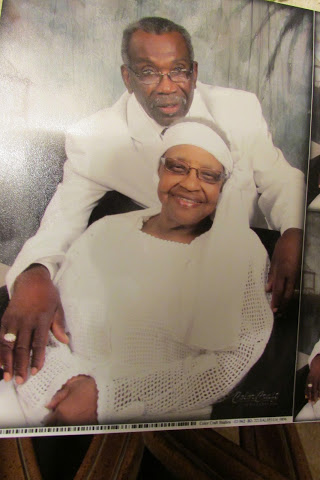

And Vera Booker, still active in her church and community, continues to believe that the future holds great promise.

"I never saw any difference between myself and my white neighbors," said Booker, the oldest of 13 children. "My blood is just like theirs. God made all of us, we are all somebody. I am just as important as you are. Christ died for all of us."

Christine S. Weerts is based in Selma and works in Christian ministry.