We all know that the recovering alcoholic’s fight is a hard one.

But we can’t possibly know how hard until we see the world through their eyes, which is something I happened to do last year, in a way, thanks to Lent.

I gave up booze for Lent last year. For me, that meant parting company with beer and wine, a couple of times a week.

Why’d I give them up? I’d read a Catholic commentary on Lent and its meaning. What we surrender in Lent is not so much about punishment or penance, but anticipation of Easter, and feeling or reminding ourselves of what Jesus gave up, so we can be in the frame of mind and heart that we need to be in. Giving up beer and wine would serve nicely, I thought, because I knew I’d be offered it relatively frequently.

I was wrong. I wasn’t offered it frequently. I was offered it all the time.

Let’s start with a seemingly innocuous trend that I’m sure most of us have noticed: in American cities, if people want to get together after 5 p.m., for a business chat or a rendezvous with a friend, the suggestion that’s always either #1 or #2 is “let’s grab a drink.” Booze is at the heart of what must be some vast percentage of after-work get-togethers.

So at the beginning of my booze-free Lent, when I was asked by a friend if I wanted to “grab a drink," I said “how about we make it dinner instead.” Deal. That night, I told the nice waiter who was inquiring about drinks that, for me, water was fine. He said, “You’re sure I can’t interest you in some wine, a nice red with your pork loin?” I thanked him, said no, and then briefed him on my Lenten observance. He sighed, but not with disappointment. It was a sigh of relief, having found a fellow traveler. We bonded for five minutes, because he, too, had foreswarn sauce during Lent.

And that was nice. But the evening’s telling detail was the fact that when I’d said I just wanted water, he’d wondered if he could still get me some wine. He asked twice. It’s not his fault. It’s de rigeur for waiters. And I understand the economics of it. They make their tips off the total sale, and both wine and beer hike the tab exponentially. For waiters, turning water (orders) into wine (orders) means a salary hike. And as a result, the beer, wine, and alcohol industry has it good. Very good. Every day, starting probably at about 3 p.m., all over the world, servers are explicitly offering the drinks industry’s wares, coaxing patrons to have a second glass, and encouraging fans of just water to man up and get something a bit more adult with their steak.

This constant offering of alcohol is part of a social phenomenon I now call The Booze Gauntlet. Gauntlets of course were corridors of people that you ran through, sustaining their withering blows as you did so. That’s why Booze Gauntlet is a good name. Everywhere you go, it’s there, and you have to run it. Servers suggesting wines. Hours that qualify as “Happy” because they feature liquid fortification. Friends who gather after work and can’t believe that you don’t want to have a beer when everyone else is having one. TV commercials rubbing your nose in the life-enhancing power of booze. Billboards and magazine pages featuring insanely bright smiles and moments of joy, all of which are obviously fueled by firewater.

Newly alert to the Booze Gauntlet because I was now consciously shielding myself from it, I started to anatomize its parts and tally its blows. And that led to a new level of sympathy for the recovering alcoholic, and a deeper admiration for his or her ability to stay sober in the face of this omnipresent pressure to drink.

A curious thing about the Gauntlet is that it’s really only apparent – you can really only see its features clearly – when you’re not drinking at all. The fact that you now say “no” on the occasions where you previously said “sure, why the heck not,” opens your eyes to the fact that at nearly every turn, alcohol is being offered, suggested, sold, poured into our mouths, or drip-fed into our subconscious.

Especially if you travel a lot. Or live in a city.

I’ll tell you about just one day of travel I experienced during Lent last year, as a kind of Day in the Life of the Gauntlet.

I began the day in Washington D.C., at a local coffee shop, seated at the bar. The folks next to me were having bloody marys and mimosas. Two rounds. On Tuesday. At 10 a.m. I marveled at it. The barrista (who was slinging booze as well as coffee, which I guess technically makes him more of a bartenderista) told me “oh, those two having bloody marys are nothing, I’ve gone through five gallons of alcohol already this morning.” Yow. And then I noticed what was in front of me…

I thought of the recovering alcoholic. Sipping his coffee in a seemingly neutral zone while being smart-bombed all around by the artillery of his temptation. At breakfast!

I left the coffee shop. A few doors down, another café advertised its Sangria Brunch. When did plain old regular brunch become so blasé that its enticements and blandishments needed to be spiced up with Sangria?

I headed to the airport for my flight to California. Airports are of course prime Booze Gauntlet zones. They’re littered with causeways that channel people past ads for alcohol and open-air bars where the booze is flowing and the standard timelines of alcohol consumption have gone topsy-turvy. Most of us have stared wide-eyed as we hurry to an early morning flight only to see folks at bars drinking pints at 8 a.m. In just one terminal on this day, around lunch time, I walked by three open bars and counted, just in passing, 23 visible pints of beer, 8 glasses of wine, and about 14 random cocktails.

And the airport Booze Gauntlet was just getting started. As I approached my gate, I passed this duty-free menagerie:

I boarded my plane. And because I’d tallied many miles and been upgraded to some kind of enhanced passenger class, I was rewarded with the special dispensation and reward earned by the elite traveler. A book on Plato? A velvet pillow? A handshake? No, a free cocktail. I declined it.

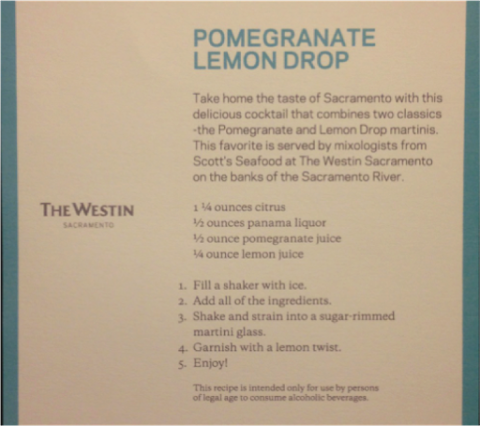

Opening the seemingly innocuous inflight magazine, I was greeted with this:

Thumbing through the pages, I conducted a quick booze census. A twenty-page stretch of the magazine had fourteen separate images of people happily drinking. One hotel did away with the humans altogether. Its half-page ad consisted simply of a picture of three thin-stemmed cocktail glasses full of some delish concoction. The message was clear: what you work hard for and what you’ve earned after months of office drudgery are these three glasses of alcohol. A good time is a boozy time.

Heroin addicts don’t get tempted with their poison in the pages of inflight magazines. But alcoholics do. Thanks to the Gauntlet.

I arrived in California still early enough to head for a coffee shop for an afternoon cuppa. After passing a handful of Budweiser trucks on the highway, I arrived at a hip joe joint, which I assumed would be a reprieve from the Gauntlet.

Not so.

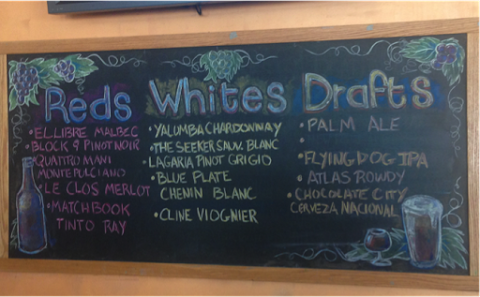

Inside, right above the bar at the entrance, was a huge sign saying “Join us tonight for our handcrafted brews and ask for our specials.” To my left, booze had completely colonized the blackboards, squeezing out the indigenous coffee offerings altogether. When did coffee shops add alcohol to their menu? I guess when they faced the fact that the margins on booze were better. As I paid, near the register I saw another small promotional sign saying the shop had won some award for

best coffee and beerjoint. Hmm, I didn’t even know that was now formally a genre of restaurant. Another blow from the Gauntlet.

Sipping my coffee in the shop’s outdoor patio, I overheard one of my neighbors recounting a story about being on a party bus where “they were pouring shots the whole night. It was the best night ever. We stopped at all these bars. But at this one place, I got left by the bus, because I was too wasted.” Alcohol doesn’t always bring out the best in us. But man oh man, do we love to talk about it. Even when the story we’re telling is about how cruel booze was to us, or how badly we abused it. It occurred to me that what this young woman was relating was basically a horror story. But that’s the power of the sly grip booze has on our lifestyles – we think those horror stories are somehow also evidence of the good time we must have had.

Next up on this day’s travel itinerary: checking in at my hotel. The friendly associate at the front desk said, “welcome, and thank you for being a platinum guest with us… when would you like your complementary glass of champagne?”

“Never,” I said, with a smile. I then told her about my Lenten battle plan, and she said “wow, that must be tough.” Which is what a lot of people say. So, let’s think about this… if we all feel that it’s so tough for a non-alcoholic temporarily giving up a couple beers a week, then what do we truly think about what we expect recovering alcoholics to do – i.e. give it up forever when they crave it more than the rest of us do? And why don’t we spend more time thinking about how hard we make it on them?

I was trying to think if I’ve ever encountered a host at a party who said “before I offer you wine, are you a recovering alcoholic?” Nope. And it’s not their fault. It just isn’t done. I myself don’t do it. But maybe I should. The point is that we have all kinds of sensitivities built into our culture for every conceivable kind of person grappling with even the slightest challenge or personal difficulty. And yet for the class of people facing one of the harder challenges, not only do we not have special sensitivities, we go the other direction and actually make it harder for them by waving their poison in their face all day long.

I was reflecting on this when I entered my hotel room that day, and smiled as I looked on the bed and saw the following card:

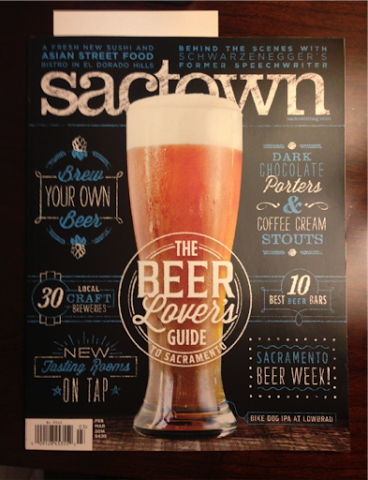

Next, my smile matured into a laugh when I looked at the nightstand and saw the following magazine cover.

In all of this, though, I’m not saying the recovering alcoholic’s lot in life is all pain and struggle. One of the huge upsides to zero booze is that it becomes mathematically impossible to drink too much, and your odds of a hangover dip to a permanent 0%. (Let’s remember that the root word in “intoxicated” is “toxic.”)

I’m also not saying that the booze industry is evil. (Although there have been a couple moments in my life when I thought “Demon Rum” a pretty fitting appellation). After all, George Washington distilled whiskey. And Holy Week – Lent’s crescendo – is packed with powerful cameos performed by wine, including that moment when the good folks at the foot of the cross sopped a sponge in wine, skewered it with a reed, and held it up to the dying/living Jesus.

I’m just saying the booze industry is awfully good at what they do – i.e. get us to drink massive amounts of their product. And they’re so good, that they inadvertently make the recovering alcoholic’s road a tough one to hoe.

But it’s not just the booze industry that’s responsible for creating The Booze Gauntlet. We all are — the spirits industry and the civilians who buy its wares and innocently guzzle them out in the open. We’re responsible for the habits we have which have made it OK to wave so much alcohol marketing in everyone’s face all the time, and the ways we’ve tacitly agreed to what we’re being told – that happiness and relaxation and socializing must involve beer, wine, liquor. Those messages and cultural credos are happily embedded in our subconscious because we let ourselves absorb them and believe them.

The ads selling these messages are everywhere, because the drinks industry’s marketing coffers are always full. And why are they always full? Because we fill them.

So, allow me to offer a sincere tip of the hat to the sober alcoholic. You run The Booze Gauntlet daily, withstanding a withering barrage and showing immense strength of will. And nobody throws you a parade for doing it.

But maybe that’s what’s needed. A ticker tape parade on a newly created Sobriety Appreciation Day. The only challenge would be finding a stretch of street in a major city that isn’t lined with bars.

Christian D’Andrea is a documentary TV producer/director with The Story Foundry, making the kind of TV that he thinks Mark Twain would make if he were alive today and in the TV business. Like the stories he tries to tell, he’s also launched startup ventures — like GodsTweets.com and SoldierFuel.com — that are designed to inspire.